- News

- Reviews

- Bikes

- Accessories

- Accessories - misc

- Computer mounts

- Bags

- Bar ends

- Bike bags & cases

- Bottle cages

- Bottles

- Cameras

- Car racks

- Child seats

- Computers

- Glasses

- GPS units

- Helmets

- Lights - front

- Lights - rear

- Lights - sets

- Locks

- Mirrors

- Mudguards

- Racks

- Pumps & CO2 inflators

- Puncture kits

- Reflectives

- Smart watches

- Stands and racks

- Trailers

- Clothing

- Components

- Bar tape & grips

- Bottom brackets

- Brake & gear cables

- Brake & STI levers

- Brake pads & spares

- Brakes

- Cassettes & freewheels

- Chains

- Chainsets & chainrings

- Derailleurs - front

- Derailleurs - rear

- Forks

- Gear levers & shifters

- Groupsets

- Handlebars & extensions

- Headsets

- Hubs

- Inner tubes

- Pedals

- Quick releases & skewers

- Saddles

- Seatposts

- Stems

- Wheels

- Tyres

- Health, fitness and nutrition

- Tools and workshop

- Miscellaneous

- Tubeless valves

- Buyers Guides

- Features

- Forum

- Recommends

- Podcast

feature

Wind assisted: a day at the Boardman Performance Centre

My triceps are killing me. And I’m already mentally hunting through the bottom drawer of my shed cabinet to see if there are any 40cm bars in there, as a 45km/h wind blows white noise in my ears. A day at the Boardman Performance Centre has taught me a great deal. And some of the lessons I’ve learned are maybe not the ones I expected. Although in retrospect, it all looks surprisingly simple.

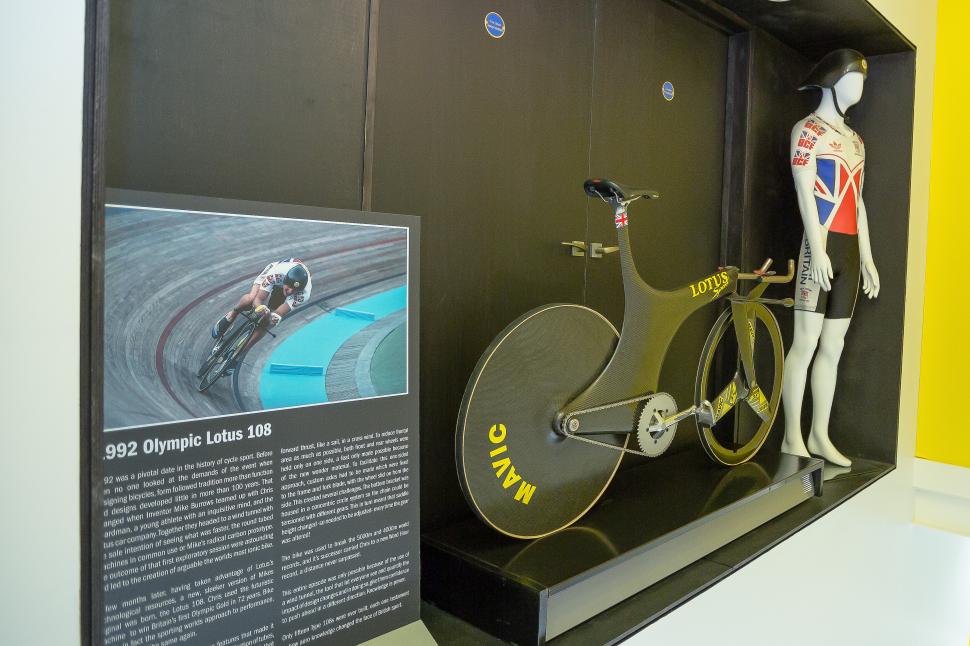

Back in 1992, when Chris Boardman piloted the revolutionary Lotus 108 monocoque bike to victory at the Barcelona Olympics, the Lotus Formula One team’s wind tunnel expertise was central in creating a bike – and an on-bike position – that manages to look modern even now. It seems incomprehensible now that Boardman was so much quicker than his gold-medal-race opponent that day, Jens Lehmann, that he actually caught him before full distance. It wasn’t just about the bike, but Great Britain’s first cycling gold medal in 72 years was firmly rooted in an analytical approach, and the track success Team GB has achieved since has come off the back of countless hours not just of training, but measuring. Adjusting. Iterating.

The best wind tunnel in the vale of Evesham

Skip forward to 2019 and Chris has his own wind tunnel, sitting on an unprepossessing retail park off the back of Evesham, next door to Fat Face. It’s about the most incongruous location for a wind tunnel you could think of. It’s not just a wind tunnel either: the Boardman Performance Centre has a physiology lab, where your body is fully put through its paces and your current fitness can be accurately benchmarked. And in the biomechanics lab your flexibility can be assessed, and super-accurate positioning, saddle pressure and pedalling sensors help to ensure you’re in position to transfer what power you have to the road as efficiently as possible. You can buy a bike downstairs, too.

All in all it’s a facility at the very highest level, and that’s borne out in some of its clientele: The HUUB-Wattbike track team have spent some long hours fine-tuning here, and they’re busy setting world records. But the Centre is the culmination of a project whose aim was to bring that laboratory expertise within the reach of normal riders, whoever they may be and whatever their goals. And it has; if you want to use the multi-million-pound facilities then it’s just a case of booking your slot.

And should you? Well, I’m your guinea pig for that journey. I’m a big guy who loves road riding, and cake, and racing a bit in the third cats. You may or may not consider that to be normal or average, but realistically I’m a middle-of-the-pack finisher in the sportives I do (except in Italy, where I’m last), and not first to the top of the climbs in group rides. I ride a range of test bikes, so I kind of know how to set a bike up, but I’ve never had a professional bike fit. I’m not as fit as I should be, or as light as I could be. I’m plenty average. Like all of us, I’d like to be a bit less average. How can I improve? How much free speed is available? What are the things to focus on? And is it worth it, for normal mortals like me?

Getting optimised

When I walk in to the biomechanics lab Bianca, the bike fitter and physio at the Performance Centre, is waving a big stick around in what looks like some kind of occult ritual. It turns out she’s just calibrating the cameras on either side of the room, and when that’s done a Wattbike that’s been set up to exactly match my current bike – a Boardman SLR 9.6 – is placed in between them.

The first thing to talk about is goals. The aim of this process is to make me a more efficient rider. But there’s no point fine-tuning a position you can only hold it for five minutes if your goal is completing the Etape du Tour: it won’t be any good for that. I do a wide range of riding, but realistically being efficient matters most to me when I’m trying (and often failing) to stay in a crit race. The races are less than an hour, and within that there are periods when you can relax a bit, so I don’t need a position that’s comfortable for the whole hour, but one I can drop into when I need it most: when I’m sitting in the wind, which I avoid as much as I can.

Before I get covered in sticky Velcro and sensors for the cameras there are some off-the-bike tests to go through. Bianca zeroes in on one aspect of my physiology for immediate attention: my feet. I’ve got high arches, and that means that I’m not using the whole of my foot to transfer power. The solution for this is simple: custom insoles formed around my foot shape. It’s an easy enough process to create them: you sink your feet into an aerated bed in a corrected position, and then the air is pumped out to take an exact mould of your foot shape, into which you press a pre-heated insole. Everything sets firm and you’re good to go.

Insoles are a very common part of the process, and a very effective way of improving your efficiency on the bike. And it’s not just the feet they affect: Bianca shows me the before and after pressure maps from the saddle sensor on the Wattbike. My saddle pressure has evened out left to right, and moved back so it’s properly centred over my sit bones. If you struggle with saddle issues, it might not be your saddle that’s actually the problem: it might be your shoes.

On the bike there are two main changes for me. My saddle height is about right but the saddle is too far back, which closes up the hip joint and makes a more aggressive position less sustainable. Moved 20mm forwards I’m hitting the downstroke of the pedal cycle at a more efficient angle. It also feels more natural, like I’m in the bike rather than on it. They don’t sound like big changes, but it’s astonishing just how different a bike can feel if you move the contact points even a little bit. 10mm further forward it all felt wrong again, with too much weight on my hands like I was falling over the front. So even if you already have the right size bike, there’s a lot to be gained from fine tuning your position.

Secondly, there are some amendments to be made to the bars and stem. I’m a big lad and I ride a big bike, and those bikes come with nice wide bars. The SLR 9.6 has a 44cm bar in the XL size I ride, but if your goal is to be more aerodynamic then reducing your frontal area is crucial. If I can be comfortable – or comfortable enough – on a narrower bar, then that’s some speed for free. Bianca’s main task is to balance the biomechanics with the changes that are likely to be more efficient in the wind tunnel. The best case scenario is that you’re in a more optimised position that’s just as efficient biomechanically, or you can make biomechanical gains that are aero-neutral. Sometimes, she says, the aero gains can be sufficient that they outweigh a small biomechanical disadvantage from being in a more aggressive position. It’s very much a balancing act.

It turns out I’m pretty adaptable, really. The insoles have given me a more stable base for my pedal stroke, and moving my saddle forward hasn’t affected my pedalling efficiency, measured by the Wattbike peanut at around 83-84, which is apparently very good. All that time being schooled by TrainerRoad to work on my pedal phases has obviously had the right effect. Swapping out the 44cm bars on the Wattbike for some 40cm ones initially feels a bit odd, but It’s certainly something I could cope with, and it doesn’t adversely affect my efficiency. A longer stem is okay, too – that stretches me out a bit more and gets me lower on the bike – but when we start moving the front end of the bike down it starts to make me noticeably less efficient, so a full-on slam is not something that’s going to work for me. With the learnings from the lab, it’s time to sit in the wind for a bit.

Go with the flow

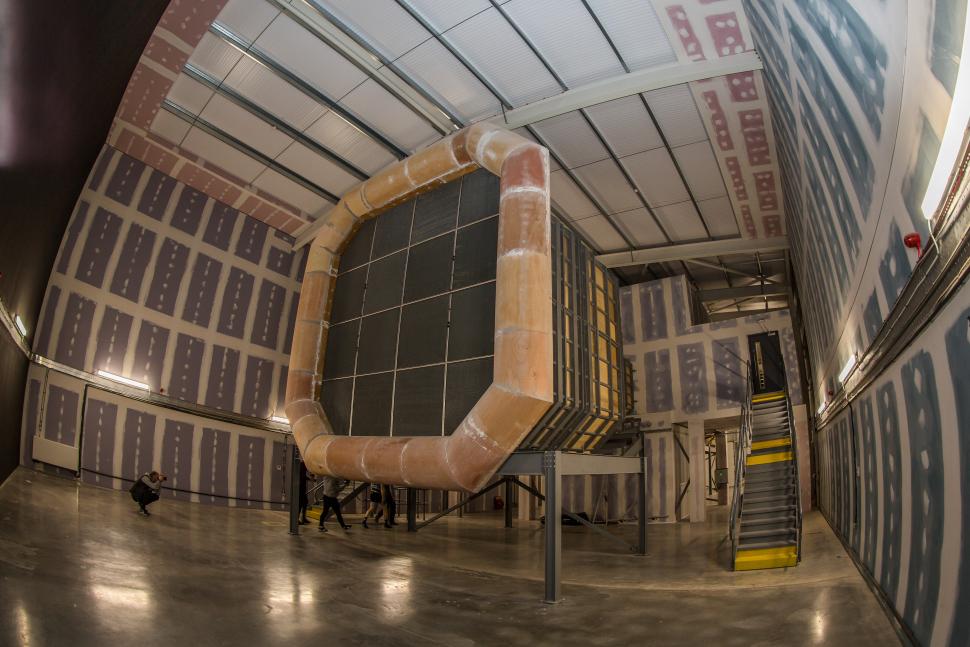

When someone says ‘wind tunnel’ to you, you’re probably thinking of just that: a tunnel. In reality the bit you put your bike in at the Boardman Performance Centre is a sort of big square room. The airflow through the middle is precisely calibrated and monitored. You can stand around and chat in the rest of it.

What you probably don’t think about is the rest of it. The room you do your stationary ride in is just a small part of what is a really, really big machine. Your bike is sitting on top of a bank of powerful computers, and between a powerful fan and an air intake the size of a small house that filters and funnels the air to create an even flow across the myriad of sensors. And all of that is housed inside a massive barn; the wind tunnel is a closed system, so the room needs to contain all the air that the tunnel can use, accurately controlled for temperature and humidity. And the tunnel can simulate speeds of up to 80 kilometres per hour, so that’s a lot of air.

The first thing to do is to get some benchmark readings with the bike set up just as I brought it. The tunnel is running at 45km/h: that’s a quick pace but not an unusual one for the kind of racing I do. The faster wind speed will amplify any differences in setup: the power you need to generate changes in a cubic relationship with your speed, so if you’re moving twice as fast through the air you’ll have to work eight times as hard.

Riding on the hoods at 45km/h, Barney, the head of science at the Performance Centre, calculates that I’d need to put out 515W to maintain it. That’s a lot of watts. Looking at my power curve, it’s a level of effort I might reasonably sustain for about two minutes. On the drops the figure is 498W: better, but not great. He doesn’t sugar-coat it: my drag numbers, he tells me, are bad.

The main metric we’re looking at is CdA: coefficient of drag area. There are two factors: the coefficient of drag, which is a measure of how slippery you are as a shape; and area, which is the amount of surface that is being acted upon by the wind. So consequently there are two things you can do to reduce it: be more slippery, or present less frontal area. I’m a big rider, in a non-optimised position, and my CdA numbers are high: 0.37 on the hoods and 0.36 on the drops. By way of comparison, Bradley Wiggins’ CdA on his hour record attempt was somewhere under 0.2. I’m not going to get anywhere near that, but Barney sets me a more realistic target of 0.3. I ask him if that’s likely. He’s non-committal: let’s see.

The first thing that changes is my saddle position, moving forwards by the 20mm we tried in the lab. This is more of a biomechanical change but actually it puts me in a slightly more efficient position, saving 11W at 45km/h. The bike already has a 130mm stem, and sadly there aren’t any pro-issue 140mm ones in the spares drawer, so that’s an intervention for another time. Swapping the bars out would eat into the testing time too much, so instead we try a virtual narrow bar position where I’m resting my hands inboard of the levers. Another 11W is shaved off my total that way.

Moving through the gears

These aren’t huge savings, but there are more and bigger to come. Barney works me through a range of positions on the hoods, dropping my elbows into a more aggressive shape and then into the position beloved of pro riders in the breakaway: hands on the top of the hoods, forearms horizontal. There’s a reason they do this: it’s a very efficient position, minimising the frontal profile of your arms and dropping your back too. Compared to my 515W baseline I’d require just 441W to keep up 45km/h, a saving of 74W.

It comes at a price though: just keeping in position for the three or four minutes it takes to spin the wind tunnel up to speed and get a minute’s worth of data is murder on my triceps. It’s not currently a sustainable position. That’s not to say it couldn’t be in the future, but it might require some significant time investment doing boring tricep dips to build up the muscles required to hold it.

Briefly we try out a virtual tribar position – arms straight out and elbows resting on the centre of the bars – and this is the most efficient position of the day, and the only one that sneaks under Barney’s 0.3 CdA target. I’m almost 100W more efficient like this. It’s not by accident that it’s the position favoured by time triallists, track pursuiters, triathletes and ultradistance racers alike. For me it’s not really an option: you can’t have aero bars in a race, and you’d be disqualified if you adopted that position without them. Barney asks the question: if the breakaway position isn’t sustainable, and the virtual tribar position isn’t allowed, what’s the next best alternative? We move down to the drops, and into a position that’s more aggressive than my starting one.

Within the tunnel there’s a projector, and on the floor in front of you you can see your position from the front and the side, as well as a live readout of your drag. Barney pegs a marker on the drag meter that corresponds to the breakaway position on the hoods, and asks me if I can ride in a sustainable position in the drops to replicate that number. The answer? Not quite. My CdA in the position I can hold is 0.32, a hundredth of a point higher, and to ride at 45km/h I’d need to be pushing 448W. But look how far we’ve come: that’s a power I could hold for five minutes instead of two, in a position I could easily hold for that long too. One of the most useful things to come out of the tunnel session is this: I may not be able to hold a position for the entirety of a crit race, or a club ride, or a sportive. But crucially, I know what it feels like, and I know what it saves me. So when it matters, I can employ it. That’s a performance boost, sure, but it’s also a psychological one.

You might expect a wind tunnel session to consist of a lot of is-this-hat-better-than-this-hat tinkering. And, if you’ve dialled your position right in previously, there are gains to be made there. The wind tunnel has a variety of helmets and skinsuits to try, and which one works for you will be dependent on your physiology and style of riding. There is, Barney says, no one skinsuit or helmet that’s always better.

After all the work on my position there isn’t masses of time to experiment with clothing, but a Bioracer aero road suit gives a useful 9W saving over the road.cc kit I started in. And on the helmet front a Uvex EDAero lid – that I already use for racing – is worth 4W over a Lazer Z1. Curiously, the Z1 with the Aero shell – a cover designed to improve aerodynamics – performed worse than it did without. Although that might be down to the fact that I find it too hot, and I’ve dremelled some vents in the front…

Putting it all together

The Aero fit as a whole was a hugely beneficial experience. My main take-home points from the experience were twofold. Firstly, even if you’re generally happy with your position on the bike, an expert eye can certainly help to make it better. The effect of just a new pair of insoles on my pedalling biomechanics was a bit of a revelation, as was the difference that small positional changes can make to the overall feel of the bike.

In the wind tunnel it’s not really a surprise that you create less drag if you make yourself into a smaller, more slippery shape. But the magnitude of the gains available just from simple changes was certainly an eye-opener. By far the biggest gain is just from adopting a more aggressive position on the bike, with the saddle further forward and the elbows more bent. That drops the power I’d need to output to maintain 45km/h in the drops from 498W to 448W, a massive 10% saving. There’s another 11W to be gained by switching to a narrower handlebar, and 13W to be had from a skinsuit and an aero helmet over normal road clothing. These gains aren’t as big, but they’re still part of the overall picture: everything adds up to 74W at 45km/h, which isn’t far off a quarter of my Functional Threshold Power – the power I’d nominally be able to hold for an hour – of 310W. I’d be over a minute quicker over ten miles, or I could ride 2.5km/h faster for the same effort.

Obviously in real-world riding there are a hundred other factors to be thrown in. Most of the time I’m not riding that quickly, and as the speed drops so does the benefit. At 40km/h you could expect about 70% of the saving, at 30km/h only about a third. If you’re riding in a group then much of the aero gain is negated by the drafting effect from the riders in front of you. And there’s also the fact that I couldn’t sustain the most effective positions for the duration of a whole ride. But it has opened my eyes to the wider picture of cycling dynamics. I’ve been known – haven’t we all? – to half-fill a water bottle for a shorter ride to save weight, or obsess over an FTP that goes up or down by a few watts. We all like to have the nice aero frames, and the posh wheels. But in comparison to the efficiency savings you can make simply by being in a good position on the bike, biomechanically and aerodynamically, those things seem like a mere bagatelle. How much difference can it make to an ordinary cyclist? Lots. We’re ripe for optimisation, us choppers. Give it a go.

About the Boardman Performance Centre

I completed an Aero Fit (https://www.boardmanbikes.com/gb_en/performance-centre/core-services/aero-fit.html) session, which normally takes around four and half hours and costs £695.

Fitting for custom insoles (https://www.boardmanbikes.com/performance-centre/core-services/siddas-footbeds.html) normally takes an hour and a half, and costs £95.

Wind tunnel sessions start from the Aero Experience (https://www.boardmanbikes.com/gb_en/performance-centre/core-services/aero-experience.html) at £195, which includes 30 minutes of time in the tunnel.

A full bike fit (https://www.boardmanbikes.com/performance-centre/core-services/bikefit-road.html) without the wind tunnel time costs £275.

We didn’t delve into the physiological side of things on our day, but health and fitness sessions start from £195 for a one a half hour Rider MOT session.

https://www.boardmanbikes.com/gb_en/performance-centre/packages/

Dave is a founding father of road.cc, having previously worked on Cycling Plus and What Mountain Bike magazines back in the day. He also writes about e-bikes for our sister publication ebiketips. He's won three mountain bike bog snorkelling World Championships, and races at the back of the third cats.

Latest Comments

- David9694 3 sec ago

Cyclists should be made to have insurance etc https://www.thetelegraphandargus.co.uk/news/24757516.four-vehicles-seize...

- A V Lowe 31 min 34 sec ago

On a bus the driver has a fully glazed double set of doors that give a direct view of any cyclist or pedestrian travelling right into the left side...

- matthewn5 56 min 55 sec ago

A friend in my cycling club has a new Ribble Allroad, I think the model with 105, and when I asked how he was finding it (before reading this...

- Rendel Harris 1 hour 6 min ago

Well yes but that's if you're looking at an equation x = n x 3 where n is any number less than 5. If you're looking for a number that is three...

- check12 2 hours 23 min ago

Get them back? They've never gone away for me, cheap tdf winning bikes on eBay with rim brakes and cheap rim brake aero wheels, just don't tell...

- Simon E 3 hours 6 min ago

It used to be called Buy Nothing Day as a protest against the the Black Friday discounting madness. The constant BF adverts, promos and stuff...

- chrisonabike 5 hours 22 min ago

Apologies - you're quite right! Something about presentation and comprehension...

- wtjs 5 hours 42 min ago

You can find out whether they're lying about 'taking action' by asking them what they actually did. When they refuse to tell you, citing various...

- chrisonabike 10 hours 27 min ago

Also don't forget - Sustrans are a charity *....

Add new comment

7 comments

Just read this again, linked from another article. It's very interesting, such a shame the Boardman centre has closed.

Has started me wondering if some narrower aero bars might be a relatively easy and cheap win of some watts, vs some fandangled wheels.

Really enjoyed reading that. More technique and science based stories would be a great distraction from the shite that's all too prevelent in the media/country/world at the moment.

I'd love to see the centre and get a session in, once funds and time allow. In the meatime, I'd better get going again with the tricep dips that I've let slip for a couple of years now. Perhaps I could develop kamtail shaped arms to offset the broad shoulders and fluffy legs. I'll put a set of 40cm bars on the wishlist too for my fantasy bike build.

Great article. Nice to see someone needing a lot of power to sustain 45Kph. Always thought I was oddly brick shaped.

Quick correction : drag/air resistance is proportional to the square of speed, not the cube. Power is proportional to speed cubed, because power is force x velocity. So at double the speed you’re doing 4x more work to move a given amount of air (ie for each metre travelled), but you’re moving twice as much air per second, which is where the extra power of two comes from to make it a cubic relationship with power. So to use the same phrasing as the article, you are overcoming 4x the drag but overcoming it twice as quickly.

Interesting cDA too. My estimate from on-road testing seems to be about 70% higher than the best values on a road bike and begins with a 4. Must be my hairy legs.

*Heads off to the the gym to add back and tricep work to the conditioning plan...

As per the forum thread a while back, I'm really interested by the massive savings given in the 'virtual TT' position. Its not particularly clever on busy roads or traffic/groups, but the anicdotal feeling of its faster is backed up by some science! Plus its so much easier to hold than the arms flat on the hoods position.

Did they tell you that the beard needed to come off?

they didn't, but it would probably save me a watt or two

Glad to hear somebody else getting tired on the tops and bent elbows position - thats why Ive raised my bars so I can get in to a bent arm position on the drops which is more sustainable.