- News

- Reviews

- Bikes

- Accessories

- Accessories - misc

- Computer mounts

- Bags

- Bar ends

- Bike bags & cases

- Bottle cages

- Bottles

- Cameras

- Car racks

- Child seats

- Computers

- Glasses

- GPS units

- Helmets

- Lights - front

- Lights - rear

- Lights - sets

- Locks

- Mirrors

- Mudguards

- Racks

- Pumps & CO2 inflators

- Puncture kits

- Reflectives

- Smart watches

- Stands and racks

- Trailers

- Clothing

- Components

- Bar tape & grips

- Bottom brackets

- Brake & gear cables

- Brake & STI levers

- Brake pads & spares

- Brakes

- Cassettes & freewheels

- Chains

- Chainsets & chainrings

- Derailleurs - front

- Derailleurs - rear

- Forks

- Gear levers & shifters

- Groupsets

- Handlebars & extensions

- Headsets

- Hubs

- Inner tubes

- Pedals

- Quick releases & skewers

- Saddles

- Seatposts

- Stems

- Wheels

- Tyres

- Health, fitness and nutrition

- Tools and workshop

- Miscellaneous

- Cross country mountain bikes

- Tubeless valves

- Buyers Guides

- Features

- Forum

- Recommends

- Podcast

PMP cranks 2.jpg

PMP cranks 2.jpgL-shaped cranks — explore the crazy idea that just won't die

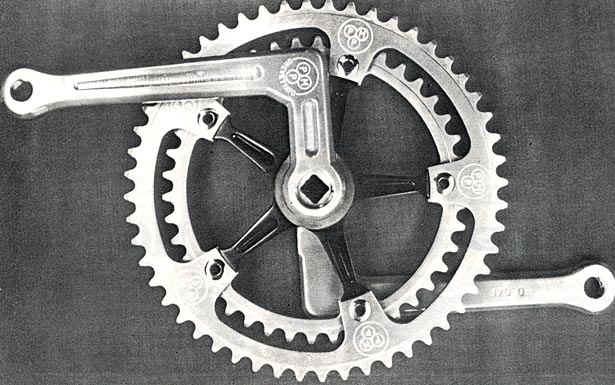

Image: PMP cranks by robadod from LFGSS [This feature from the road.cc archive was last republished on October 15, 2020]

We take a look at one of the more bizarre technical aberrations of recent history: the wackiest cranks ever made.

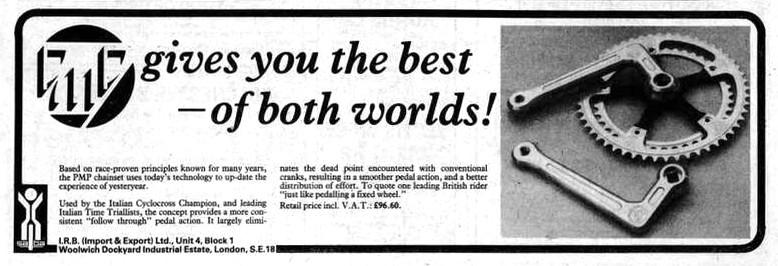

In 1981 Cycling Weekly magazine published a favourable review of an unusual new crank. The magazine gave a set to “a first-category Surrey roadman to try them out.”

The write-up said: “He fitted them in March and although our test is now over they are still on his best road bike. He has come to prefer them to orthodox cranks.”

CW’s tester “enjoyed the ‘feel’ of the cranks and reported that the slower his pedalling speed the more advantage he felt, which is perhaps why they are finding favour with big-geared time triallists.”

The tester told CW: “I didn't just get the power on the downward strokes of the pedals but all the way round the pedalling revolution as at low pedalling speeds dead centre seemed to be removed. This helped me keep a steady rhythm particularly when sitting back in the saddle climbing hills.”

He didn’t feel the same benefit when pedalling quickly in a low gear, though.

CW concluded: “So there is the verdict, whatever the theories, in practice our roadman tester felt the PMP cranks offered an advantage – and surely that is the true criterion.”

That crank was the PMP Brevettato. Its unusual (but, as we’ll see, by no means unique) feature was a right angle bend about a third of the way between the bottom bracket axle and the pedal.

PMP made some interesting claims about the Brevettato cranks. They included:

- The unique form of the PMP pedal crank means improved distribution of the energy required in pedalling and a perfectly round stroke; the result: increased equilibrium.

- Its L-shaped design increases the pedal's propulsion power and lessens energy dispersion on the downstroke.

- Pedalling the PMP way means to be perfectly in the saddle; in fact, the bicycle rider is forced to lean back slightly more than usual, putting him in the best possible aerodynamic position.

- The PMP pedal crank means that pedalling is no longer an "ankle game" since the bottom dead-point is lightened to allow greater ease on the upstroke.

- Bicycling becomes a pleasure and not a chore because the PMP pedal crank and its unique features take away the exertion and lighten muscle strain.

Bold claims, and with Cycling Weekly’s Surrey roadman finding they eliminated dead centre, you have to wonder why the design isn’t now ubiquitous.

That’s simple: it’s all bollocks.

A crank is a lever. The torque you generate when you load up the end of a lever depends on just two things: the force you exert and the distance between the point where that force is applied and the pivot.

Nothing else matters, especially not the route the lever takes between the two points. It can be a straight line, a right angle bend or any other shape; it doesn’t matter. All you achieve by making a crank any other shape than straight is to add weight and flexibility.

PMP cranks were even marked with the distance between the crank and pedal holes. As the Bicycle Museum of Bad Ideas remarks: “somebody at PMP understood it was simply an odd way to make a 175mm crank”.

Pretty much everyone who was paying attention in physics at school pointed this out at the time, but that didn’t stop a fad for PMP Brevettatos, especially among time triallists.

Even the great 80s time triallist Ian Cammish used them. Cammish, who won the Best British All-Rounder contest nine times in the 1980s, mentioned them when he tried to sell one of his 1983 bikes on eBay in 2013.

“Unfortunately the PMP cranks cracked a long time ago,” he wrote.

They had a bit of a reputation for that, though to be fair so did many other high-end cranks of the era.

Perhaps because of these reliability issues, and because not many were made in the first place, PMP Brevettato cranks are now rare and collectible. The most recent set I’ve seen on eBay went for US$400 — almost £300.

Other wonky cranks

The bike industry has a serious problem with knowledge loss, which leads to people who really should know better reinventing bad ideas over and over. The PMPs weren’t the first non-straight cranks (the earliest seem to have been in 1897), nor the last. Like the monster lurching back to life at the end of a bad horror movie, wonky cranks keep coming back.

Want to make people go “What the hell?” get yourself a set of dpardo Sickle Cranks:

It’s not at all clear what advantages dpardo claimed for this design. PMP had a slight case of ‘Campagnolo spoken here’ Italglish, but dpardo really needed to get a native speaker of English to write its marketing copy. It says — and I swear I haven’t changed a letter of this:

58T gear turns once is 1.6M faster than 50T!As same as pedaling 50T !Same pedaling force pedal 58T, the riding performance is 16% increasing than 50T with normal cranks

The craziest recent reappearance of wonky cranks has to be Z-Torque cranks, which came and went between 2010 and 2014.

The shape was claimed to have come to inventor Glenn Coment in a dream. He bent a wire coat hanger into the same shape and “when he revolved it in his hands he found that this crank assembly was different from any other crank assembly ever made. Except for top dead center and bottom dead center, this crank had no dead spots. He was amazed. And in future testing would find that during a rider's maximum effort, power increases at a bikes rear wheel of 20-25% were possible.”

If true, that would be little short of astounding.

Z Torque further claimed “many advantages, including”:

- Smoother pedaling

- More power to climb hills

- Less perceived effort to pedal

- Faster acceleration

- Less affected by headwinds

- Ability to turn higher gearing

However, the Z Torque was really just another crank that connected the bottom bracket axle and pedal by a circuitous route, with an extra problem baked in.

As you can see, the long arm of the V shape, is really, really long. Imagine trying to pedal while banked over hard in a corner and you can probably explain why Z-Torque cranks were never even as popular as PMP Brevettatos.

John has been writing about bikes and cycling for over 30 years since discovering that people were mug enough to pay him for it rather than expecting him to do an honest day's work.

He was heavily involved in the mountain bike boom of the late 1980s as a racer, team manager and race promoter, and that led to writing for Mountain Biking UK magazine shortly after its inception. He got the gig by phoning up the editor and telling him the magazine was rubbish and he could do better. Rather than telling him to get lost, MBUK editor Tym Manley called John’s bluff and the rest is history.

Since then he has worked on MTB Pro magazine and was editor of Maximum Mountain Bike and Australian Mountain Bike magazines, before switching to the web in 2000 to work for CyclingNews.com. Along with road.cc founder Tony Farrelly, John was on the launch team for BikeRadar.com and subsequently became editor in chief of Future Publishing’s group of cycling magazines and websites, including Cycling Plus, MBUK, What Mountain Bike and Procycling.

John has also written for Cyclist magazine, edited the BikeMagic website and was founding editor of TotalWomensCycling.com before handing over to someone far more representative of the site's main audience.

He joined road.cc in 2013. He lives in Cambridge where the lack of hills is more than made up for by the headwinds.

Latest Comments

- Hirsute 8 min 17 sec ago

First thing to check is whether this applies to NI.

- matthewn5 21 min 55 sec ago

Thanks @Rendel, I'll look into them - they compare well with the Terreno Zeros that I already tried:...

- David9694 23 min 34 sec ago

Our car-dominated urban environment is repressive and hot - let's see if we can desecrate the countryside

- chrisonabike 25 min 4 sec ago

Are you confusing a clearly opinionated - nay, biased rag like road.cc with a balanced, respectable news organisation like the BBC?

- Hirsute 1 hour 28 min ago

Car spreading https://climatevisuals.org/carspreading/ https://cleancitiescampaign.org/carspreading

- Bigtwin 1 hour 41 min ago

"Welcome to your local Council - you don't have to be a moron to work here, but it really helps if you want to blend in".

- Rendel Harris 1 hour 57 min ago

Laverack still offer the same machine in a rim brake version so the "disc" is there to differentiate it from its stablemate.

- mdavidford 2 hours 35 min ago

Quite right - get those soapboxes off our roads. As everyone knows, the right place for them is the internet.

- Bungle_52 2 hours 38 min ago

It's finally live. Here is the link :...

Add new comment

109 comments

A regurgitated article that refuses to die?

Once more, but this time with feeling

There's nowt more retro than an increasing amount of material on road.cc

Which is a shame - because it's always mostly been a well-informed and creative site.

Retro: L-shaped cranks - a bad article that just won't die...

I'd actually be curious about how this worked for in-phase cranks ie: handcycles; I have three dead spots in my rotation on my upright, with a huge one at forward bottom - main power is at backwards bottom and upwards mid, with a small deadspot in the middle, then a small power spot in upwards-forward before we're dead again.

... In other words, from my right side so we're clockwise; 6o'clock to about 9/10 is my main power phase, using my entire core to pull towards me;

then a small dead spot, then power through to about half-one pushing upwards and forwards with my middle back and shoulders.

Mostly dead spot through to 3, using biceps and shoulders, dead-spot through to about five, small power through to six.

I wonder if having the cranks tipped back a bit with non-standard geometry might help with the dead spots a bit - I think an oval ring would likely have more effect, though. I suspect I'd end up with my cranks jammed against my thigh more often with non-straight cranks, though.

They were supposed to eliminate the top dead centre dead zone. If your pedal dynamics / technique are right, you don’t need L shaped cranks. They may have some benefit to people who ‘flat foot’ around the entire rotation, but unless you really haven’t got a scooby, or your carrying some sort of ankle problem, that’s not many people. TL;DR they are a shit idea.

There is no benefit. So long as the pedal hole and the axle hole are fixed in relation to each other, it doesn't matter a fig what shape the metal in between is.

Oh I love this. Could not wish for a clearer example of the shortcomings of typical tests reviews. In this case we can all laugh at the reviewer. And yet so many reviews repeat exactly, precisely, the same methodological error - rely on the reviewer's own human bias and subjective opinion and write it up as some kind of valid finding.

They were great for 'flat footers'. Nowadays the pedalling techniques have improved, you can't 'roll your foot around the stroke' / pedal in circles with L cranks. They were an interesting idea, which has now been consigned to the dustbin of 'strange solutions to the problem of inefficient human leg levers when cycling'.

Apparently if you repeat something enough, in these parts, it becomes true. No matter how much bollocks is included.

That's getting a vinyl release:

https://grizzlybomb.com/2019/03/01/buffys-once-more-with-feeling-getting...

These won't help at all, they do nothing, may even make things worse as the actual crank arm looks like it might stick out more - not sure on that. It's a really interesting question though.. i'd definitely have thought a non-circular chainring might be able to help, although the actual profile may need to differ from a leg-cycling one to cope with the different dead spot timing. Power data with a decent sampling rate would help.. wonder if anyone has done any work on this ? Going to have a look, good luck with your search.

Go on then, I’ll bite.

Why do they have some benefit? How are they mechanically different to any other crank?

It does matter, but not in a good way. A bend in the crank will flex more.

Well, now I've got something to sing about

https://youtu.be/Sv8uRVLN5Dc

There has been a small amount of research done; the shape currently believed to be most optimal is egg shaped.

Good luck shifting gears, though.

Having had a think about these, I suspect it would just move the deadspot in terms of position on the rings; the position of my power and dead zones, in relation to the position of my hands, probably would not change, and the change in position of my arms in relation to my shoulder would likely move (think knees, arms want to be in a fairly narrow envelope), probably outwards which would increase agility but reduce power.

they really don’t have any benefit worth talking about. The L shape just means that you could eliminate top dead centre power dip, without having to change the angle of your foot relative to the ground. It’s far easier ( and more effective) to learn how to pedal correctly.

Bunnies aren't just cute like everybody supposes!

They've got them hoppy legs and twitchy little noses!

And what's with all the carrots?

What do they need such good eyesight for anyway?

buffy-once-mayhem.jpg

No. One more time - it makes no difference. Other than increasing the weight and maybe decreasing rigidity.

Egg shaped? Do you mean the chainring? Reminds me of the old biopace chainsets from the late 80's. Never tried one, so can't comment on those.

L shaped cranks won't make an iota of difference to the applied turning moment though

The turning moment applied by the foot is the same regardless of the shape of the lever. This only adds weight to the design. I would further hazard that it increases flex in the crank, therefore reducing efficiency (albeit minimally) and adding potential weakness and possibility of failure.

I thought these were an April fool, are they actually marketed?

Hmmm. Central disc brake...

Fit to axle inside the spokes, operate by bluetooth? No need for wires hydraulics as self contained unit...

Comes with free Ratbollock essence

Gents, would any of you be interested in some Nigerian real estate I currently inexplicably have laying around? Going cheap!

To whom do I email my card details?

me

I still have a limited amount of Snake Oil and brightly coloured Magic Beans at clearance prices.

what is the purpose of this article.? or comments about it? or this comment? this is all pointless.

Perhaps nostalgia, or a chance to snigger at the scientifically illiterate who thought this would work. Or maybe a light hearted diversion from the endless stories of people being knocked off their bikes, which seem to dominate roadcc these days.

L-shaped helmets offer 853% more protection against being knocked off your bike, studies reveal.

I'd like to see some analysis of the physics of ordinary crank lengths.

Is it the case, for example, that for steep climbing a longer crank would be a good idea, as less force is needed to achieve the same torque (due to the longer lever)?

Pages