- News

- Reviews

- Bikes

- Accessories

- Accessories - misc

- Computer mounts

- Bags

- Bar ends

- Bike bags & cases

- Bottle cages

- Bottles

- Cameras

- Car racks

- Child seats

- Computers

- Glasses

- GPS units

- Helmets

- Lights - front

- Lights - rear

- Lights - sets

- Locks

- Mirrors

- Mudguards

- Racks

- Pumps & CO2 inflators

- Puncture kits

- Reflectives

- Smart watches

- Stands and racks

- Trailers

- Clothing

- Components

- Bar tape & grips

- Bottom brackets

- Brake & gear cables

- Brake & STI levers

- Brake pads & spares

- Brakes

- Cassettes & freewheels

- Chains

- Chainsets & chainrings

- Derailleurs - front

- Derailleurs - rear

- Forks

- Gear levers & shifters

- Groupsets

- Handlebars & extensions

- Headsets

- Hubs

- Inner tubes

- Pedals

- Quick releases & skewers

- Saddles

- Seatposts

- Stems

- Wheels

- Tyres

- Health, fitness and nutrition

- Tools and workshop

- Miscellaneous

- Cross country mountain bikes

- Tubeless valves

- Buyers Guides

- Features

- Forum

- Recommends

- Podcast

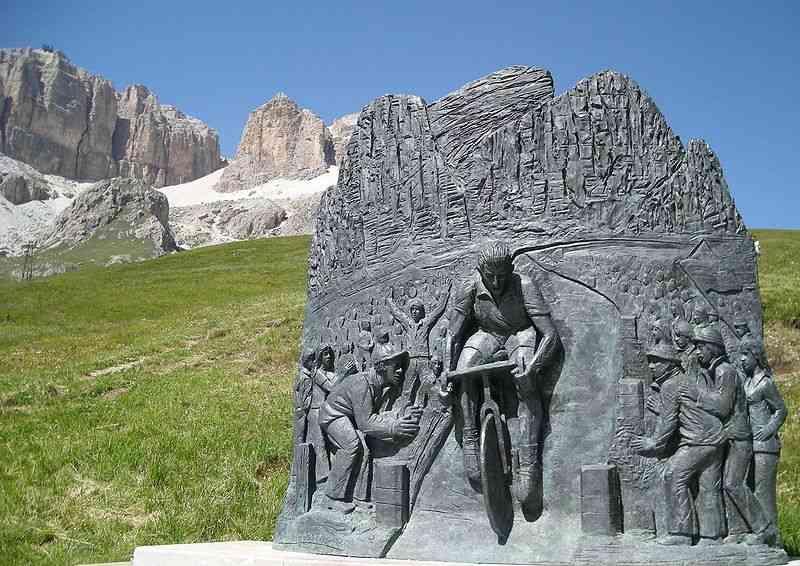

Fausto Coppi (copyright Ji-Elle:Wikimedia Commons).jpg

Fausto Coppi (copyright Ji-Elle:Wikimedia Commons).jpg50 years on: Italy remembers Fausto Coppi

Italy has this weekend marked the fiftieth anniversary of the death of one of cycling’s true greats, Fausto Coppi, with a series of events in his birthplace, Castellania, the town where he lived much of his life, Novi Ligure, and Tortona, where he died from malaria on 2 January 1960 at the age of 40.

Yesterday morning, a mass in Coppi’s honour was held in the small church in Castellania. The service, relayed to crowds in the piazza outside on a big screen, was attended by his children, Marina and Faustino, Andrea Bartali, son of his greatest rival, several surviving cyclists who rode alongside him, and dignitaries including Angelo Zomegnan, director of the Giro d’Italia.

In the afternoon, proceedings moved to Tortona, with the launch of a book dedicated to Coppi and a film in which the people of Tortona remembered him. From there, the scene shifted once more to Novi Ligure, where in the Museo dei Campionissimi, which commemorates both Coppi and six-time Milan-San Remo winner Costante Girardengo, journalist Beppe Conti hosted a discussion about his life and legacy. Finally, this afternoon, a cyclocross race was held in Coppi’s honour, on a two-kilometer circuit starting and finishing in front of the museum.

Naturally, the 2010 Giro d’Italia will be paying its own homage to Coppi to mark the anniversary, including a stage finish in Novi Ligure. The rider is already commemorated each year by the race’s highest point being named the Cima Coppi – the ‘Coppi Summit,’ which this year is on the Passo di Gavia at 2,618 metres.

A glittering career

Coppi’s exploits are the stuff of legend, and although to remember seeing him in his prime, you’d need to be in your seventies now, he consistently tops polls to name Italy’s greatest athlete across all sports.

His palmarès speak for themselves. He won the Giro d’Italia five times – a record held jointly with Alfredo Binda and Eddy Merckx – and the Tour de France twice in three attempts, plus a string of one-day races including the Giro di Lombardia a record five times, Milan-San Remo – whose route takes in both Tortona and Novi Ligure – three times, Paris-Roubaix and the Flèche Wallonne and, in 1953 crowned his career with the World Championship.

In Milan in 1942, he also set a world record for the hour, 45.798km, a distance that would not be bettered for 14 years until beaten in 1956 by Jacques Anquetil. The bike that Coppi rode to set that record is now in the cycling shrine of the chapel of Madonna del Ghisallo, near Como, whose bells ring out each year when the Giro di Lombardia passes by.

Yet veteran Italian cycling journalist Rino Negri, who as a youth guided Coppi on training rides in the hills of the Oltrepò Pavese wine-growing area south of Pavia, said that Coppi himself steadfastly refused to single out any of his achievements as being greater than any other. “You should say the best things,” the cyclist told him, “not the best thing. There isn’t one exploit that’s greater than another.”

Had the Second World War not caused the suspension of the Tour de France for seven years and the Giro d’Italia for five, the likelihood is that Coppi, the consummate all-rounder, leaving rivals in his wake on ascents as well as in breakaways, sprints and in time trials, would have added still further to that already impressive list. Certainly, between 1946 ad 1954, he was almost untouchable, with the French cycling journalist, Pierre Chany, saying that during those years, once Coppi got free of the peloton, he was never caught.

The link from cycling's past to present

Coppi was in many ways bridge between the romanticised, heroic days of pre-war cycling and the more technical-focused, tactical racing of the modern era. He watched his diet, followed a strict training regime including putting early-season kilometers into his legs ahead of the spring classics, and made sure he dressed appropriately for the conditions. His technique was flawless, with contemporary accounts stating that he was the most elegant rider ever seen.

The new tactics that Coppi introduced also saw the role of the gregario - the Italian term for domestique - evolve, from one of near-serfdom to the team leader to playing a much more important part in how races unfolded, something that endures to this day, although as his team-mate Ettore Milano said, “he was always our captain, but he never behaved as if he were our boss. Each time he asked for something, first he’d say ‘please,’ then afterwards, ‘thank you’”.

Meanwhile, his great rivalry with Bartali, and the scandal that would later engulf his personal life, mirrored the fractures and growing pains within Italy itself as it recovered from wartime defeat and the accompanying struggle between fascists and partisans and transformed itself into a republic as it rushed headlong towards the years of the economic miracle and La Dolce Vita.

The early days

Born on 15 September 1919, and baptised Angelo Fausto Coppi, the youngster fell in love with cycling at an early age. The fourth of five children, he was beset by ill-health in his early years but by the age of eight he was already in trouble at school for playing truant to ride a rusty old bike, missing its brake blocks, that he had found in the cellar of his family home. Leaving school at the age of 13, he worked as a butcher’s delivery boy in Novi Ligure, meeting other cyclists and developing an interest in racing, which led to him buying his first bike with the help of his father and uncle.

That purchase was not without its tribulations, however. Coppi later recalled how he had set his heart on a 600 lire, made to measure frame he had seen advertised in the paper by a shop in Genoa. Taking the train to the port city, Coppi placed his order and handed over the money. Promised that the frame would be ready within seven days, the youngster returned the following week, only to be told it wasn’t ready. Each week for two months, he travelled to Genoa, and each week returned home disappointed, and out-of-pocket for the train fare.

In the end, Coppi settled for a ready-made frame, not the made-to-measure one he’d set his heart on, feeling that the shopkeeper couldn’t be bothered to put in the work on a custom frame for a youngster from up in the hills. Nevertheless, his new bike enabled him to win his first race at the age of 15, for which he won a salami sandwich and 20 lire. By 1938, he had taken out a racing licence, winning his debut race, this time receiving an alarm clock.

In 1938, Coppi met Biagio Cavanna, an ex-boxer who had become a masseur after losing his sight, and who counted a number of cyclists among his clients, who suggested he turn “independent” – a class of rider able to compete against professionals and amateurs, and by the following year the cyclist was winning races by margins measured in minutes rather than seconds.

Coppi leaves team leader Bartali in the shade in Giro debut

His astonishing rise was sealed in 1940, when he won the Giro d’Italia at the age of 20, but it was also a race that marked the beginning of his great rivalry with Bartali. Coppi had, in fact, been signed at the start of the year to ride for Bartali’s Legnano team as a gregario in Italian. Bartali was the star name in Italian cycling, having won the Giro twice and the Tour de France once between 1936 and 1938. The following year, he won Milan-San Remo, a feat he would repeat in 1940.

Initially, Bartali believed that the tall, thin Coppi was too slightly built to cope with three-week stage races, but he was to be proved wrong during that year’s Giro d’Italia in a manner that both astonished and enraged him.

After Bartali had crashed on the opening day, Coppi alone among the Legnano squad had proved able to ride alongside his leader as attacks from other squads took their toll on other members of the team. Then, on Stage 11, Coppi chased down and caught a breakaway, eventually winning the stage by four minutes. Although Bartali marshalled the remaining members of the team to catch him, it was Coppi who took the overall win in his maiden Giro.

But within 24 hours of Coppi completing that victory, Italy had entered the Second World War, meaning that he would not have an opportunity to defend his title until 1946.

Enlisting in the army, Coppi was sent to North Africa in March 1943 and captured by the British a month later. His experience as a prisoner of war add to Coppi’s mystique; he shared plates and cutlery with the man who would later father Claudio Chiappucci, who finished three times on the podium of both the Tour de France and the Giro, without winning either, and gave haircuts to British soldiers including an amazed British rider, Len Levesley, who recognised Coppi from cycling magazines.

Giro and Tour post-war doubles follow Milan-San Remo success

It was after the war that Coppi really came into his own. After his release, he traveled home by a mixture of cycling and hitch-hiking, and returned to racing in July 1945 in the Circuito degli Assi in Milan. Naturally, he won. The following spring, he won his first Milan-San Remo, where he was one of nine riders that broke off the front in the opening five kilometres of the 292km race. Coppi left his fellow escapees behind on the ascent to the Passo del Turchino, and eventually won by 14 minutes from the Frenchman, Lucien Teisseire.

In 1949, Coppi became the first rider to win the Giro d’Italia and the Tour de France in the same year, a feat he repeated three years later. That 1949 Giro victory included what many believe to be his greatest ever victory, on the stage from Cuneo to Pinerolo, 20km or so southwest of Turin, when he attacked early on and won after a 192km solo break, leaving Bartali 11 minutes down the road. His performance in that year’s Tour de France was equally imperious. By the time the race arrived in Paris, the Italian was half an hour ahead of the entire field with the exception of his compatriot and rival, Bartali.

The 1952 Tour de France was one of the highlights of Coppi’s career. That year’s race included the first-ever ascent of the Alpe d'Huez, which Coppi won after attacking six kilometers from the summit. By the time the Tour arrived in Paris, Coppi was almost half an hour ahead of the field, and prize money for other places had been doubled by the organisers to keep the rest of the field interested in the race.

Rivalry with Bartali divides a nation

During those post-war years, Coppi’s rivalry with Bartali divided Italy, with fans claiming to either be coppiani or bartiliani, Coppi representing the forward-looking, secular, industrial north, while Bartali – nicknamed ‘il pio’ (the pious), while hailing from just outside Florence, found his greatest support in the conservative, rural and religious south.

It was said that the riders often seemed more interested in beating each other than winning the race itself. In the 1949 World Championships at Valkenburg in The Netherlands, both abandoned the race, rather than assist the other, earning each a three-month ban from the Italian cycling association.

One of cycling’s most iconic photographs shows Coppi apparently passing a bidon to Bartali on the Col d’Izoard in the 1952 Tour de France, suggesting that the relationship between the pair was getting warmer, but the riders disagreed over who had actually offered the bottle, and even today, debate persists over whether the picture was genuine or staged for the press.

But in later years, the rivalry would mellow, the pair appearing together on TV variety shows, singing duets, with Bartali’s lyrics containing knowing references to Coppi’s use of amphetamines, not banned at the time. Coppi himself, when asked in a TV interview if he ever took the substance, replied, “whenever necessary.” When pressed as to how often that meant, he added, “almost all the time.”

Tragedy and "the Woman in White"

Two factors contributed to Coppi’s decline during the 1950s. First, there was the death of his brother Serse, also a professional cyclist, in 1951 following injuries sustained in a crash during the Giro di Piemonte. Secondly, in 1954 Coppi’s personal life became embroiled in scandal through his association with Giulia Occhini, more often referred to as ‘the Woman in White.”

Coppi had met Occhini in 1948 when her husband, an army captain named Enrico Locatelli, a huge fan of Coppi, had taken his wife, who knew nothing of cycling, to see him racing. By chance, their car was caught up in a traffic jam behind the one in which Coppi was traveling, and it appears that for Occhini, it was love at first sight.

Occhini, typically dressed in white, hence her nickname, began attending Coppi’s races alone, and it was clear the attraction was reciprocated with the cyclist, despite being married with a daughter, spending more and more time with her.

In 1954, the affair went public after the newspaper La Stampa published a photograph of Coppi embracing Occhini following a race in St Moritz, Switzerland. With Italy still in many respects a deeply conservative country where adultery was considered scandalous, the relationship provoked outrage.

The pair moved in together to an apartment in Tortona, but the landlord threw them out. Fleeing the press, they stayed briefly in a hotel, moving again once reporters had tracked them down to a house Coppi bought in Novi Ligure. Even there, they were not free from censure, the police raiding the property at night to ensure they were not sharing a bed.

Even the Pope intervened, urging Coppi to return to his wife and refusing to give his blessing to the Giro d’Italia when the rider took part in it. Coppi’s wife, meanwhile, refused to consent to a divorce, still illegal in parts of Italy and highly taboo even where it was lawful. Occhini even had to travel to Argentina to give birth to their son, Faustino, to ensure that he could bear his father’s name, which wouldn’t have been the case had he been born in Italy.

His brother’s death and the scandal surrounding his relationship with Occhini both took their toll on Coppi. By the late 1950s, he was said to be taking drugs to help him through every race, and even criterium organisers were reducing the distance of races to ensure that he could complete them.

The mosquitos' bite…

Coppi seemed destined to join the ranks of bloated ex-pros, living on tales of past glories – although, of course, he had more to remember than most – until fate intervened following a trip to Upper Volta, now Burkina Faso, in 1959 at the invitation of the country’s president to take part in some bike racing against local riders as well as a hunting excursion.

Among the other big-name European bike riders taking part in the trip were Jacques Anquetil, Louison Bobet and Raphaël Géminiani, with whom Coppi shared a room. Later, Gémianini would recount how he and Coppi had spent a night in a room infested with mosquitos. Both contracted malaria, and while Géminiani survived, Coppi, whose doctors insisted he was suffering from bronchopneumonia – a misdiagnosis that would lead to questions being raised in the Italian parliament – died.

With him in the room when he passed away was his faithful gregario, Milano, who said that Coppi’s last words were, “give me some air.” Milano, who had handed his team leader water bottles countless times during their racing days together, this time replaced the spent oxygen cylinder by Coppi’s bedside, but the campionissimo had already breathed his last.

Latest Comments

- ROOTminus1 1 sec ago

That's a complicated one, the bridge would be easily and cost effectively maintained by joint Plymouth City and Cornwall County Councils'...

- Paul J 11 min 5 sec ago

Dries isn't really pronounced anything like the english "dries" (as in, in the process of drying). It'd actually be almost exactly the same...

- chrisonabike 17 min 58 sec ago

A bit of a tangled web here. It may be safer driving * but people who cycle more and drive less can enjoy much better health (inc. just "feeling...

- ROOTminus1 18 min 31 sec ago

I understand your point, I just see it as being evidence that cars should have speed limiters and it should be an offence to drive without the...

- Smoggysteve 11 min 28 sec ago

The issues here are mostly caused by one single over-riding factor. Most people (by which I mean the average persons build, shape, fitness levels)...

- Surreyrider 53 min 52 sec ago

How on earth can you mark a winter tyre down for being "not as grippy or as fast as a summer tyre"? That's ridiculous logic.

- andystow 1 hour 49 min ago

I'm 53, and gained most of my cycling fitness after age 43. I've never done an FTP test nor used a power meter, but based on occasionally asking...

- ubercurmudgeon 1 hour 51 min ago

I doubt you'll need to worry about facing that particular dilemma: by the time you find yourself in need of a pump, it'll probably have fallen off...

- mdavidford 2 hours 8 min ago

Except that presumed liability is usually a matter of civil liability, so you wouldn't be prosecuted as a result of it (though you may be held...

- Rendel Harris 2 hours 57 min ago

Well, I finally got some response from my repeated requests as to what was happening with the alleged database and was supplied with a link which...

Add new comment

3 comments

Nasty disease malaria - I've got it following two years as a development worker in West Africa. You're never completely free of it. Knowledge of it isn't that great in the UK and when I had my first attack after returning to this country, I had to tell the doctor what drugs I needed a prescription for and the dosage as chloroquine wasn't available over the counter then. Some of the newer drus against malaria are pretty scary and can have some horrible side effects but the risk of not taking them is greater still. Someone I knew said she'd take anti-malarials if she got sick - but she got cerebral malaria and by the time this was diagnosed she was already in a coma. She was taken back to the UK by medivac but never regained consciousness.

i'm sure Rapha may do you a one off limited edition 'Fausto Coppi' bundle, if you wave enough of your hard earned in front of them, or possibly sell your house.

but yes, great write up of one of the sports greatest.

Great story Simon, thanks for the write up of my idol.

I love this pic of the great man; I truly plan to start dressing like this soon, I think I am old enough now...

Coppi.jpg