- News

- Reviews

- Bikes

- Components

- Bar tape & grips

- Bottom brackets

- Brake & gear cables

- Brake & STI levers

- Brake pads & spares

- Brakes

- Cassettes & freewheels

- Chains

- Chainsets & chainrings

- Derailleurs - front

- Derailleurs - rear

- Forks

- Gear levers & shifters

- Groupsets

- Handlebars & extensions

- Headsets

- Hubs

- Inner tubes

- Pedals

- Quick releases & skewers

- Saddles

- Seatposts

- Stems

- Wheels

- Tyres

- Tubeless valves

- Accessories

- Accessories - misc

- Computer mounts

- Bags

- Bar ends

- Bike bags & cases

- Bottle cages

- Bottles

- Cameras

- Car racks

- Child seats

- Computers

- Glasses

- GPS units

- Helmets

- Lights - front

- Lights - rear

- Lights - sets

- Locks

- Mirrors

- Mudguards

- Racks

- Pumps & CO2 inflators

- Puncture kits

- Reflectives

- Smart watches

- Stands and racks

- Trailers

- Clothing

- Health, fitness and nutrition

- Tools and workshop

- Miscellaneous

- Buyers Guides

- Features

- Forum

- Recommends

- Podcast

feature

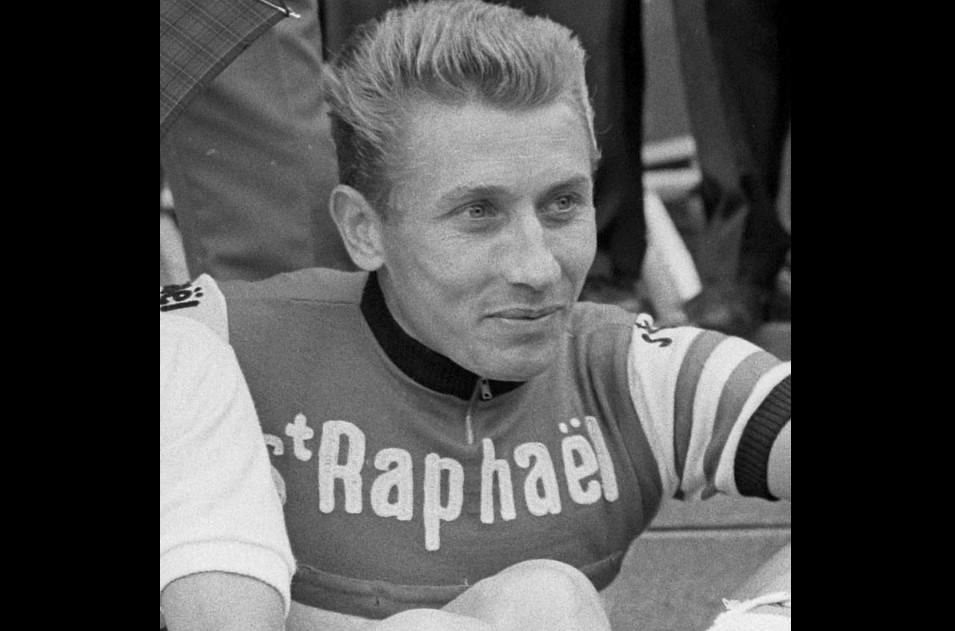

Jacques Anquetil at the 1963 Tour de France (picture via Dutch State Archives)

Jacques Anquetil at the 1963 Tour de France (picture via Dutch State Archives)Cheating at the Tour de France — a rich history dating back 120 years

The sight of a couple of dozen riders holding on to team cars as they went up the Stelvio in the Giro Next Gen under-23 race earlier this month shows that when it comes to cheating in cycling, it’s often a case of Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose – go back 120 years to the early years of the Tour de France and you’ll find riders ejected from the race for slipstreaming cars, or even taking a lift in one.

That got us thinking about some of the more egregious and bizarre forms of cheating that cycling’s biggest race has seen down the years, as well as examples of riders who have pushed the rules as far as they will go while keeping to the letter, if not quite the spirit, of the regulations that govern the race.

> A brief history of motor doping in cycling

Our selection is by no means exhaustive, so feel free to add chip in with other examples in the comments. Given the sport’s history, we’ve not addressed anything here that is drug-related – but will do in a separate article coming here shortly on road.cc.

Maurice Garin - letting the train take the strain

The Giro d'Italia may have its own train now... but riders still aren't allowed on it

The first edition of the Tour de France in 1903 saw a couple of riders sanctioned for drafting cars, plus a fair bit of skulduggery by overall winner Maurice Garin – but it was the following year that provided some of the most egregious examples of rule-breaking in the Grand Boucle’s infant years, and very nearly led to the race being scrapped altogether.

Garin, winner of the opening stage in 1904, appeared to have successfully defended – only to be disqualified, alongside 11 other riders including the rest of the top on the general classification, and the winners of all six stages, for illegally taking trains, or riding in cars, for part of the route.

His disqualification, accompanied by a two-year ban, followed a four-month investigation by the Union Vélocipédique Française (UVF) and resulted in Henri Cormet, who had finished fifth overall (and had also been warned during the race after getting a lift in a car) being awarded victory, and at 19 he remains the youngest ever winner of the Tour.

Wacky Races

That wasn’t the full extent of the cheating at an edition of the race that comes across as something akin to the 1970s Wacky Races cartoon featuring Dastardly and Muttley. During Stage 2, race officials had to fire shots in the air to disperse a 200-strong crowd that had assembled to cheer on their favourite, Antoine Fauré , with rival riders including Garin attacked and glass and nails spread on the road. Other shenanigans involved itching powder being poured into rival riders’ shorts.

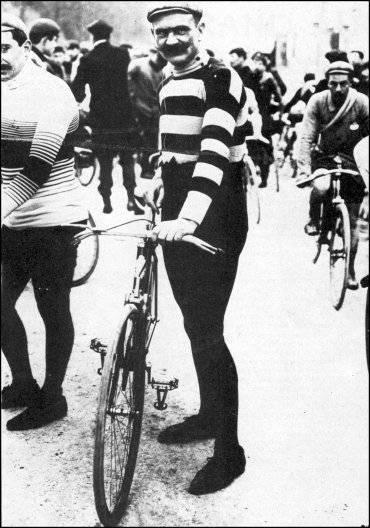

The prize for inventiveness that year though surely goes to Hippolyte Aucouturier (above), who had been forced to abandon the first edition due to food poisoning (possibly due to a drink being spiked) and who returned to the race in 1904, winning four stages, only to be disqualified for taking a tow from a motor car by – and this may put your teeth on edge – chomping down on a cork attached, via string, to the vehicle.

Eugene Christophe - a myth is forged

During the sixth stage of the 1913 Tour de France, disaster struck Eugene Christophe, who had led his rivals over the Col du Tourmalet by 18 minutes on a brutal day in the Pyrenees when he realised there was a problem with his bike and discovered his front forks had broken. With no outside help permitted, all he could do was sling his bike over his shoulder and try and find somewhere to fix it.

It’s part of Tour mythology that Christophe was thrown off the race because, despite fixing the broken forks himself, the blacksmith’s boy in Ste-Marie-de-Campin had operated the bellows for the fire, which was deemed outside assistance and thereby cheating. In fact, the watching officials only docked him 10 minutes for that – but with his rivals by now hours down the road, his chance of victory had long gone. To add insult to injury, the car that had crashed into him, causing his front forks to break belonged to the organisers.

Jean Robic - heavy metal descender

An example of pushing the rules as far as they could go to gain an edge came from Jean Robic, who in 1947 won the Tour de France the first time it was raced following World War 2. Breaking an unwritten rule (and not, therefore, cheating, albeit guilty of unsportsmanslike behaviour), he attacked the yellow jersey on the last stage to Paris, which he began third overall.

Once dispensing with the race leader, Robic then bribed the eventual runner-up to ensure his victory. He’s perhaps best remembered though for a rather innovative approach to descending, which would involve him picking up bottles containing lead from team staff at a summit, adding weight – and thereby greater speed – to his descent. Once organisers got wise to what was happening and banned solid metal, he switched to mercury. Many copied him, but Robic was the pioneer.

Anquetil’s broken gear cable

Bike changes ahead of a major climb aren’t an uncommon sight these days – but at the Tour it’s only been permitted since 1964, except where the bike being ridden developed a mechanical problem. The previous year, it had been a broken gear cable that allowed Jacques Anquetil to swap bikes to a lighter, lower-geared model ahead of the Stage 17 climb of the Col de la Forclaz in the Swiss Alps.

If that seems like fortuitous timing, with Anquetil going on to clinch his fourth overall win, there was a reason for that – the ‘snapped’ gear cable was a trick devised by Anquetil and his team manager, Raphael Géminiani to get around the rules. Anquetil would win the stage from Federico Bahamontes and take the yellow jersey from the Spaniard ahead of winning the race in Paris four days later.

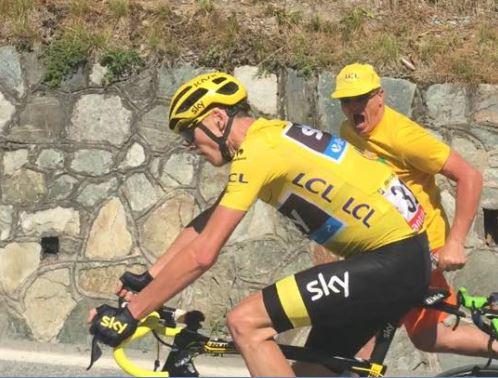

Froome has a hunger bonk

Stage 18 of the 100th Tour de France in 2013 saw eventual winner Chris Froome extend his lead over his rivals on his way to succeeding team-mate Bradley Wiggins as champion – although it could have been a disastrous day for the Team Sky rider had it not been for a deliberate decision to break the rule regarding not being allowed to obtain food or drink in the closing 10km of the stage.

> Chris Froome nearly cracks on Alpe d'Huez

On a stage that included an unprecedented double ascent of the Alpe d’Huez, Froome was flagging badly as the race tackled the famous hairpins for the second time. With 5k left, he sent Richie Porte back to the team car for an illegal gel and water bottle – the calculation no doubt being that the penalty imposed by the race jury would be less than the time he’d have lost without refuelling.

As we said at the top, this article aims to look at aspects of cheating within the Tour beyond those associated with doping, which has always been a feature of the race, and came close to threatening its existence with the Festina affair that broke 25 years ago at a time when drugs cheats dominated the race – an issue we’ll be looking at in more detail soon, but if in the meantime you have your own favourite examples of (non-drugs-related) cheating at the Tour, please let us know in the comments below.

Latest Comments

- mitsky 35 min 52 sec ago

Is it any wonder that drink driving is still a problem when the police do nothing even with clear evidence like this: https://youtu.be/hw071PAofHQ

- Rendel Harris 42 min 22 sec ago

Such as, for example, saying: "It’s made from two types of fabric: super-loud yellow (orange is also available as a colour option, as is pink in...

- Mr Blackbird 47 min 22 sec ago

Possibly, but I think there will still be a time delay between receiving a warning and looking and the brain processing the image.I guess cycling...

- chrisonabike 2 hours 21 min ago

Indeed - but again these are perhaps questions we should keep asking. Even if the immediate answer is "well we are where we are" or "how on earth...

- Surreyrider 3 hours 15 min ago

Specialized aren't that American. Merida owns something like 49%.

- wtjs 4 hours 9 min ago

Then smash bad driving behaviour very hard...

- David9694 8 hours 46 min ago

Calls for Oxfordshire transport chief to resign blocked...

Add new comment

2 comments

Whereas that's now something that only happens on commutes...

Isnt it funny how we look down on some forms of cheating but fully accept and even embrace others. The assistance from a moving vehicle (aka sticky bottle) springs to mind. The only time i have ever booed anyone in a sporting event was watching someone being pulled up Caerphilly mountain in the Tour of Britain a few years ago, so blatant and obvious that you have to wonder what other form of cheating these people commit. At least there has been a clamp down on the "magic spanner" con.