- News

- Reviews

- Bikes

- Components

- Bar tape & grips

- Bottom brackets

- Brake & gear cables

- Brake & STI levers

- Brake pads & spares

- Brakes

- Cassettes & freewheels

- Chains

- Chainsets & chainrings

- Derailleurs - front

- Derailleurs - rear

- Forks

- Gear levers & shifters

- Groupsets

- Handlebars & extensions

- Headsets

- Hubs

- Inner tubes

- Pedals

- Quick releases & skewers

- Saddles

- Seatposts

- Stems

- Wheels

- Tyres

- Tubeless valves

- Accessories

- Accessories - misc

- Computer mounts

- Bags

- Bar ends

- Bike bags & cases

- Bottle cages

- Bottles

- Cameras

- Car racks

- Child seats

- Computers

- Glasses

- GPS units

- Helmets

- Lights - front

- Lights - rear

- Lights - sets

- Locks

- Mirrors

- Mudguards

- Racks

- Pumps & CO2 inflators

- Puncture kits

- Reflectives

- Smart watches

- Stands and racks

- Trailers

- Clothing

- Health, fitness and nutrition

- Tools and workshop

- Miscellaneous

- Buyers Guides

- Features

- Forum

- Recommends

- Podcast

feature

Is your FTP lying to you? Why lactate profiling could be the future of physiological testing for cyclists

There's almost unanimous agreement that using training zones is the most effective way to progress as a cyclist, but how can you be sure your zones are correct? For years I used a functional threshold power (FTP) test to determine mine, only to find out during a lactate profiling session that they were some way out... but what exactly is lactate profiling?

> This is why you’re not a Tour de France racer

Last year we subjected Liam to a load of tests to find out why he wasn’t (and to the best of my knowledge, still isn’t) good enough to be in the Tour de France. Well, blood lactate profiling promises to be the gold standard of physiological testing that's currently trickling down from the pros to the masses, and takes things one step further. This test allows riders to map their strengths and weaknesses as a cyclist and pinpoint their current fitness using science. Other, more basic tests could be influenced by caffeine, fatigue, or simply how well practised at it you are.

Cardiff-based fitness test experts Synergy Performance helped us run through how a lactate profiling test works, what they can tell us and why this isn’t going to be the last time you hear lactate testing mentioned in the world of cycling. Oh, and we'll also be looking at my numbers to see just how much they differed from my predicted FTP, and how far I've got to go to beat a pro...

Is lactate profiling better than an FTP Test?

Your FTP, or functional threshold power, is the highest possible power you can hold for around an hour. It's by far the most popular metric for determining training zones, and can be tested relatively easily so long as you have a power meter.

There are many different ways of testing FTP. Some coaches recommend a 12-minute test, and others a five-minute test after some intervals; but the most common are either a ramp test to failure or a 20-minute test.

Since I began training, and in an attempt to progress rather than just spinning for fun, I've always used the 20-minute test. This is where you ride full gas for (you guessed it) 20 minutes, and then multiply your average power by 0.95.

From this you can use software such as TrainingPeaks to determine your training zones. So, how can a lactate profiling test be any better?

Well, the easiest way to explain is by pointing out some of the flaws of the age-old FTP test. For example, do you do it fatigued or fresh? We all want to produce the biggest numbers possible, but are we just artificially bumping up the zones and shooting ourselves in the foot for harder sessions if the test is done totally fresh?

Then there are other external factors such as stress from work, what you've eaten in the run-up, caffeine consumption, hydration, and simply how hard you're willing to work on one particular day. Obviously, the best thing to do is to keep your testing as consistent as possible, but that's not always easy when some factors such as the weather and season we're in are well out of our hands.

One final issue with FTP tests is that you can train yourself to be better at them! When I started cycling and performing FTP tests, my pacing was horrific. I'd go out too hard and by halfway through the test, would be chewing my stem and slumped over the bars. Obviously the training I've done since has helped to boost my FTP, but how much of that figure is simply because my pacing has improved?

> How training zones can help you get your greatest cycling fitness gains

Luke Craddock of Synergy Performance highlighted that traditional power testing only shows if you've got better at riding a set duration, rather than whether you've improved across the board. Craddock explains that with lactate testing, "we are looking at improvements at a cellular level and therefore can see a shift within your physiology.

"That might be key for your event, and sometimes this occurs without any change or even a decrease over these generic 12 or 20-minute power test numbers, highlighting the importance of having a profile."

Power testing will always be limited by the fact that your training zones are based on a fixed percentage of your FTP, but not everyone is built the same. By removing this assumption it's possible to pinpoint training zones that are unique to a particular rider.

Craddock adds: "If I lactate test five riders with an FTP of 300 watts, they would all produce a different set of training zones based on how they fuel performance. This is why for a time-crunched athlete, lactate profiling is so key."

Is lactate testing a new idea?

It's no wonder, then, that lactate testing has been used in the pro peloton for 10-15 years, with Team Sky putting it to particularly good effect throughout most of the 2010s. It's clear that lactate profiling is now commonplace throughout the World Tour peloton, with no one a firmer believer than Iñigo San Millán, Tadej Pogacar's coach.

Craddock says: "A common misconception is how people assume lactate testing is only for pros. I am a believer that the more time-crunched you are, the more fundamental a profile is."

You might expect someone who specialises in lactate dynamics to say that; but the undeniable fact is that if you want to progress, and only have limited time to do it in, then each turn of the cranks has to count.

What even is lactate?

Simply put, lactate is produced when carbohydrates (in the form of glycogen or glucose) are broken down anaerobically (without oxygen) to produce energy, in a process called ‘glycolysis’.

Lactate and lactic acid aren't the same!

"A common misconception is that lactate is bad," says Craddock.

"Actually lactate, once transported back to the slow twitch muscle fibres, is turned back into ATP [a form of energy]. Understanding and profiling the concentration is key to determining how your body is fuelling exercise.

"Lactate has to be transported by the blood from fast twitch to slow twitch muscle fibres where it can be converted to energy. That's why a large part of the tests focusses on an individual's ability to clear/shuttle lactate."

He went on to explain that it's this shuttling that makes the best of the best so good, and it's something that traditional power testing could never tell you.

What's being tested (and what it all means)

> Can you get fit by cramming all of your riding into the weekend?

The testing is broken down into two tests designed to collect lactate readings when riding both aerobically and anaerobically, as well as peak and lactate clearance rates.

Using these markers at set intensities, an insight into how your energy systems are fuelling your performance can be built. In Craddock's words, this gives you "an understanding of where you currently are within your sporting journey, which is fundamental before you can plan a road map for achieving a goal."

- Aerobic threshold (LT1)

The first lactate threshold, often referred to as LT1 or 'the aerobic threshold', is the lowest intensity at which there is a sustained increase in blood lactate concentration above resting values. That's the boundary between zone 1 and zone 2 to me and you. You should then, in theory, be able to ride at this intensity for a really long time.

- FatMax power range

FatMax is kind of what it sounds like: the maximum amount of fat that an athlete can 'burn' per hour, and often considered to be the very top end of Zone 2. Because you're burning primarily fat and not carbohydrates, very little lactate is produced and hence fatigue from this training is low. This is why coaches often prescribe upper-end zone 2 training.

- Maximal Lactate Steady state (MLSS) (LT2)

Your second lactate threshold, LT2, is the intensity at which there's a rapid increase in blood lactate, indicating the point at which lactate production exceeds the ability to clear it. It is this LT2 value which is very closely related to the FTP figure.

- Anaerobic capacity/VLamax

VLa max tells us our maximum lactate production rate, and therefore the capability of our anaerobic system. VLa max is closely linked with VO2 max, and can tell us how punchy or endurance-focussed a rider is.

- Lactate clearance/shuttling ability

The body's capability to lower lactate concentrations in the blood is important in any endurance sport that requires efforts that aren't always steady-state. A poor lactate clearance ability could limit your physiological strengths within a race situation, where bursts of effort followed by quick recoveries may be required.

In simple terms, lactate profiling will give us an understanding of how my body reacts to (and recovers from) different efforts, whether they're long, short, hard or easy when out on the bike.

The tests

The profiling is broken down into two main tests. The first is to isolate the aerobic system, and the second to isolate the anaerobic system.

Test 1

The first test is similar to a ramp test, but instead of going up in predetermined steps, Craddock would review each lactate reading taken to determine the power that I should ride at next. This enabled him to ensure that a threshold wasn't missed, and pinpoint them with the desired accuracy.

The test was complete once Craddock was satisfied that my blood lactate had increased above my LT2 (Similar to FTP). This meant that although the test didn't feel easy, it did feel easier to complete than a traditional FTP test, where I'd have had to ride at above threshold for a significant amount of time.

Craddock added that this means a lactate profiling session can be achieved without being detrimental to other training sessions during the week.

Test 2

The second part of the test was a super short intense effort followed by a period of sitting, again with my lactate measured and tracked at set increments. This test helped to build an understanding of how I use glycogen as an energy source, and also my ability to clear lactate in an isolated state.

It's worth mentioning that climbing off the bike immediately after a sprint is a bizarre feeling. Craddock explained that this was necessary, as even easy pedalling would improve my lactate clearance rates.

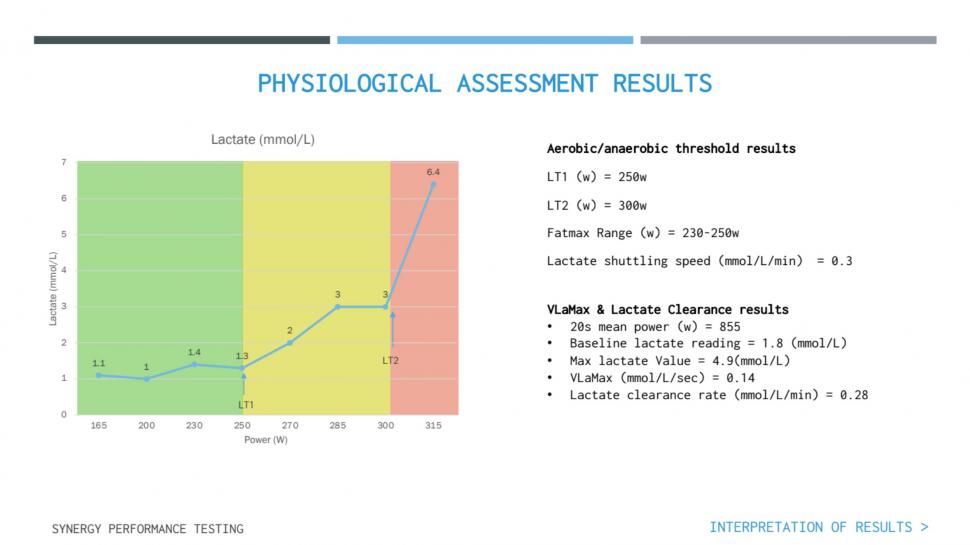

The results

> How to get the most from your limited training time

LT1

LT1, as we discussed earlier, is the point at which your body stops using fats as its primary fuel source. I was happy to find that this was a strength of mine! The fact that my body is effective at oxidising fats is probably why I can hold my own on long group rides with riders of a higher calibre than me. In Grand Tours it's this aerobic system that is arguably most important, so that riders don't ramp their lactate just sat in the bunch.

Jamie: 250 watts

UK elite rider: 275 watts

WorldTour pro: 300-320 watts +

FatMax

FatMax is the wattage that I need to sit at to burn the highest quantity of fat. Personally I'm not looking to lose weight, but this will still be an important zone to train in as it's the hardest I can ride without fatiguing my muscles too much.

Jamie: 230-250 watts

UK elite rider: 260-280 watts

WorldTour pro: 280-320 watts +

LT2

LT2 is where the lactate rapidly increases, and proved to be much lower than I expected. For my prior FTP test, I'd ridden at 350w for 20 minutes, giving me a calculated FTP of 332. However, the lactate testing pinpointed my LT2 at 300 watts, some 10% lower. This obviously has a huge impact on my training zones, and Craddock said that this is more common than you might think among experienced cyclists that are well-practised at performing FTP tests.

Jamie: 300 watts

UK elite rider: 360 watts

WorldTour oro: 380-400w +

VLamax

VLaMax typically ranges from around 0.2mmol/L/sec to 0.8mmol/L/sec. With more endurance riders being towards the lower end, and more punchy/sprinter types being towards the top end. My result shows that I am not a punchy rider at all, and if I want to do better in races or competitive group rides, then this is an area to work on.

Jamie: 0.14 (mmol/L/sec)

UK elite rider: 0.44 (mmol/L/sec)

WorldTour pro: Climber 0.2-0.5/Sprinter 0.5-0.8 (mmol/L/sec)

Lactate clearance

Finally the all-important lactate clearance rates, and the area that riders such as Pogacar and Roglic shine. Your ability to process and clear lactate is important for improving both aerobic and anaerobic capabilities, and up until now has been an overlooked metric within endurance sports due to difficulty measuring it using traditional power duration curve methods.

Jamie: 0.28 (mmol/L/min)

UK elite rider: 0.38 (mmol/L/min)

WorldTour pro: 0.73 (mmoll/L/min)

*data subject to the testing protocol used and are based upon a 70kg rider

It looks as though I have some work to do before you see me in a Grand Tour then! A Tour de France Pro could quite easily drop me before even beginning to burn carbs, or riding at a pace that might cause them some distress. My VLamax also puts me firmly on the endurance end of the spectrum, so even if I did somehow manage to make it to the end of a race with them, the chances of a final kick are looking extremely slim...

What's next?

Although a lactate profile can help map your strengths and weaknesses, Craddock was keen to get across that it's a highly effective way to monitor progression. Many of his clients will return every three months or so for repeat tests to see whether their training is working or not. If there is no improvement in the desired area, then it's a good indicator that a different training strategy should be undertaken. He added that this is particularly important for juniors coming up through the ranks who only have a limited time to make an impression.

Lactate testing might not be a new invention, but from what I've seen this is definitely not going to be the last time you're going to hear about it. I highly suspect that its prominence in the World Tour will increase. After all, if it works for Pogacar then everyone else will be keen to copy!

Then, there's the potential for real-time lactate monitoring looming on the horizon. Devices such as the K'Watch by PKVitality are already in development, and monitors like this could bring a whole host of gains for training and racing, allowing riders to monitor their effort to ensure they don't 'blow up'.

The UCI being the UCI, there's a good chance technology like this would be severely restricted or banned outright; but I'd put good money on it becoming commonplace in both amateur and professional training over the next decade. Of course, like any data, it has no real value without the ability to interpret it.

> How to maximise your fitness when you get to 40+

For now, at least, lactate testing remains primarily in labs and a session like I undertook including consultation, the test itself and the post-test report typically costs around £160. Whether that's worth it or not will depend a lot on your ambitions as a cyclist, but I would argue that if you're looking to progress then a test like this will make a far bigger difference than a fancy carbon-railed saddle.

Thanks to Synergy Performance for having us along. You can check out their services, including remote testing, on the Synergy Performance website.

Do you think lactate testing has the potential to be the next big thing in cycling? Let us know in the comments section below...

Jamie has been riding bikes since a tender age but really caught the bug for racing and reviewing whilst studying towards a master's in Mechanical engineering at Swansea University. Having graduated, he decided he really quite liked working with bikes and is now a full-time addition to the road.cc team. When not writing about tech news or working on the Youtube channel, you can still find him racing local crits trying to cling on to his cat 2 licence...and missing every break going...

Latest Comments

- Rendel Harris 1 sec ago

Mrs H suffers when wearing narrow shoes, just bought her a pair of Giro Berms which she loves and apparently are very comfortable (purchased thanks...

- David9694 20 min 55 sec ago

Car smashes into wall near Exeter Cathedral...

- David9694 30 min 44 sec ago

Driver Who Broke Runner's Spine in Three Places Praised for Waiting Around Until Help Arrived

- Steve K 1 hour 7 min ago

Even if this gets to 100,000 signatures, I suspect the Petitions Committee will simply say there has already been a debate, so no need for another...

- Prosper0 8 hours 58 min ago

Just doing the Lord's work in case anyone's interested in this product. This Mucoff Pump is a £100 rebrand of an £85 Rockbros rebrand of a £60...

- mdavidford 9 hours 47 min ago

Obviously it means 'springing out of the bunch' on a critical sector. Or maybe it's referring to the time of year.

- David9694 10 hours 35 min ago

Woman taken to hospital after flipping car onto roof in Trowbridge...

- A V Lowe 11 hours 18 min ago

Its blindingly obvious from the image that the DKE of the buses include the mirrors which extend to nearly reach the edge of the tarmac pavement on...

- Sredlums 11 hours 51 min ago

It's sad when being very good at your job - any job - isn't enough to earn a decent living. It shouldn't be that way....

Add new comment

9 comments

Consumer capitalism - it gets everywhere, eh? Into every nook and cranny of our lives.

Listen, hinny, I can tell you from decades of doing many forms of cycling that you don't need no steenkin' metrics about your bike riding. For all forms of cycling, from pootling to the pub right through to doing road races and TTs, what you need is simply to do these things.

The "training" comes automatically and is best measured against what you want to achieve (at cycling, not data collecting) including measuring yourself against others, as in road racing. You really, really don't need thousands of pounds worth of gizmos and data-anaylsis "services" to get better - and very good - at any kind of cycling you like.

In fact, there's plenty of evidence to show that data-anaysis often produces cyclist-paralysis, of the head and will rather than the muscles. "The gizmo data says I've failed so I'll give up".

Just do it, see? If you want to, you'll get better at it.

IIRC, Cav was always reported to be a rider that, just based on turbo trainer stats, would not have made any selection criteria...and yet he is the most successful sprinter the World has seen.

Out of interest, is there *anything* you think is better about the world now than when you were young?

I'm all for "just riding your bike" for fitness, enjoyment, mental well-being and all that. But I'm a bit surprised that athletes and coaches waste all this time and money on training programmes if all they need to do is "just do it", and that winning and losing is determined by the amount you "want it".

It all smacks of a certain kind of now-elderly football fan who doesn't really accept that running around a lot and lumping it into the mixer isn't the only true, British, way of playing.

Me? - I yam thoroughly modern with the odd bit of post-modern stuck on here and there, even! Yet some current stuff feels like just another consumer-bait glamourised-up to sell loadsa expensive stuff to people who really, really don't need it. They are told to see themselves as "athletes" when they are no such thing. As Guy Debord might have opined, they pay attention to (meaning spend for) the image of being a racing cyclist whist never achieving the reality of being one.

How many buyers of high-functioning race and other sporting bikes actually take part in events in which they and their helpmeets could be genuinely classified as those "athletes and coaches" you mention? A tiny percentage of cyclists on "racing" bikes (of all categories) actually take part in races, TTs or other truly sporting events. The vast majority of race-bike cyclists just ride their bikes for fitness and pleasure.

Many modern bike technologies are genuine improvements that are truly useful: disc brakes, STI gears, tubeless tyres, etcetera - I has 'em all. A lot of other current cycling paraphenelia is of use only to actual athletes who may benefit from the "marginal gains" such stuff can sometimes provide. But a lot of that stuff is actually a barrier, not an aid, to improving athletic ability. It's another set of often confusing and inchoate media between the human and reality.

And its expensive. And it soon becomes landfill. How many bike computers of all those produced are actually now used as such, rather than leaching out toxins in a landfill somewhere. One percent? Two? How many "training programs" are now defunct, old-hat and unfashionable compared to the latest and greatest set of expensive stuff thought up by some striving entrepreneur?

There is a false assumption at the heart of this article, which is that FTP, for example as determined by the (corrected) power in time-trial effort should be the single and only source of determining the intensity and duration of your interval training. This is bonkers. It is well understood that the duration for which people can hold their "FTP" varies wildly, from under half an hour to well over an hour. Not only does intelligent training increase the absolute value of FTP, but it also increases the duration for which you can hold FTP. There are good FTP protocols out there which go beyond "95% of a 20 minute effort", and depending on your training goals you may want to burn a couple of thousand calories before the effort, etc. Then you simply do the training and tune the FTP and intervals as necessary to land somewhere where the training is productive and progressive but not over-taxing.

Lactate testing can be beneficial, but it's almost useless unless you're doing it frequently (as often as traditional FTP tests) and know how to interpret the results to inform your training. Given the expense and complexity involved, I'd argue that it's likely not worth doing unless you're already being coached and are training 14h+ per week.

I dont think its a false assumption - however incorrect it is. Its the default assumption for anyone in consumer land who's introduction to structured training using FTP has been via Zwift, TrainerRoad, Training Peaks etc etc. I also suspect whilst although you are right - the reality is as a "one-size-fits-all" approach its probably a decent approximation to good.

Lactate meters/monitors are much cheaper and more available now than before. It'd be quite feasible for someone to get one and do their own regular tests (perhaps with the help of a partner).

"One final issue with FTP tests is that you can train yourself to be better at them!"

I don't think this is an issue. In a test to find out how much power you can put out over 20 minutes/an hour/whatever, pacing is an important factor. You need to be able to do it in order to improve your results in that test.

FTP is not the only relevant measure, as I observe every Zwift race I do where people with similar FTP or w/kg drop me with ease because they have better short-term power. But most of us (definitely including me) aren't racers, and I'd argue that "how hard can you keep going for quite a long time?" is an important metric for people who like riding for quite a long time.

Plus if you have a trainer and/or power meter, it's easy to do and repeat with no further hassle or outlay. A test that you don't do because it costs £160 and needs a trip to a lab doesn't tell you anything.

Pacing should be perfectly (as near as you can manage) even in an FTP test. So really, you need to do a series of them regularly (but with sufficient recovery between and the same rest pre-test, obv.) stepping up the power in each, till you fail the test. When you can't finish one, then it was above your FTP.

Really, you need a lab with a gas analyser to measure O2, and do a ramp test. No pacing involved, just a progressive, timed increase in power and the gas analyser will pin-point exactly what your peak aerobic power is.

Or use lactate. Spend (less than) £100 for a multi-function blood/glucose meter, with lactate strips. Go on the rollers. Go from very low power up in fixed steps of power. Take a series of tests at each level (get a partner to help), until you see a steady state value. At some level, you should see the steady state lactate value go up to a new level. Congrats you've found LT1.

LT1 is far more relevant for endurance athletes than FTP. Knowing LT1 tells you what your Z2 training should be. The (small, in terms of time) amount of max-effort intervals you put in can be based more on time intervals and going on feel for max power on that time. Repeat till exhaustion. Tailor the interval lengths for the race situations you're targeting.

Cost: lactate monitor and strips, ~£100. Rollers: ~£150. Powermeter: ~£600 to £1200 depending.

You'll be better informed training wise than most, on a fairly low budget.

(Dumb, cheap rollers + bike powermeter covers you for both road and test, as well as Zwift, but feel free to spend more on a fancy turbo).