- News

- Reviews

- Bikes

- Components

- Bar tape & grips

- Bottom brackets

- Brake & gear cables

- Brake & STI levers

- Brake pads & spares

- Brakes

- Cassettes & freewheels

- Chains

- Chainsets & chainrings

- Derailleurs - front

- Derailleurs - rear

- Forks

- Gear levers & shifters

- Groupsets

- Handlebars & extensions

- Headsets

- Hubs

- Inner tubes

- Pedals

- Quick releases & skewers

- Saddles

- Seatposts

- Stems

- Wheels

- Tyres

- Tubeless valves

- Accessories

- Accessories - misc

- Computer mounts

- Bags

- Bar ends

- Bike bags & cases

- Bottle cages

- Bottles

- Cameras

- Car racks

- Child seats

- Computers

- Glasses

- GPS units

- Helmets

- Lights - front

- Lights - rear

- Lights - sets

- Locks

- Mirrors

- Mudguards

- Racks

- Pumps & CO2 inflators

- Puncture kits

- Reflectives

- Smart watches

- Stands and racks

- Trailers

- Clothing

- Health, fitness and nutrition

- Tools and workshop

- Miscellaneous

- Buyers Guides

- Features

- Forum

- Recommends

- Podcast

feature

2022 Tour de France, stage 15 (A.S.O., Pauline Ballet)

2022 Tour de France, stage 15 (A.S.O., Pauline Ballet)The unwritten rules of the Tour de France - what are they and how are they enforced?

20 years ago this July, on the final climb of the final mountain stage of the 2003 Tour de France, Jan Ullrich finally looked capable of defeating his old adversary, Lance Armstrong. For arguably the only time during his seven-year-reign, the disgraced Texan appeared out-of-sorts at the Tour. Throughout the Pyrenees, with a rejuvenated Ullrich – the winner of the 1997 Tour and by this point already twice a runner-up to the American – breathing down his neck, Armstrong and his manager Johan Bruyneel’s tactics were simple: “hang on”.

And then, on that final showdown on Luz Ardiden, the yellow jersey hit the deck. Hugging a slight right-hand bend, Armstrong’s handlebars tangled with a child’s bag, sending him to the ground with a thud.

As Armstrong struggled with his pedals (and almost headbutted his handlebars) during a frantic effort to regain contact, Ullrich called a halt to hostilities in the lead group.

In his 2022 biography of Ullrich, Daniel Friebe writes that the German hero felt bound by “an unwritten cycling diktat – that, when a rival crashes or punctures, you wait, particularly if he’s in the yellow jersey.”

For Ullrich, so close to a redemptive second Tour win, the choice was simple because, as he put it after the stage, “fairness is everything in sport”. And besides, Armstrong had done the same for him after a similar incident two years before.

Following Ullrich’s adherence to cycling’s unwritten code (a gesture somewhat indicative of the honour amongst thieves which existed in the peloton during that murky era), the US Postal rider – adrenaline coursing through his veins – attacked and won the stage, and with it the Tour. Ullrich was devastated.

Seven years later, Andy Schleck was in yellow on the Port de Balès during the penultimate Pyrenean stage of the race. Schleck – the Ullrich to Alberto Contador’s Armstrong – stood on the pedals to attack. As he changed gear, he dropped his chain. Contador, who had accelerated to match Schleck’s burst, simply kept going, as his closest rival forlornly fumbled with his bike at the side of the road. Social media outrage and questionably sincere video apology aside, chaingate – as it quickly became known – effectively won Contador the Tour.

These two incidents, so similar in nature but with strikingly different outcomes, highlight that while there's a whole book of regulations that govern the Tour de France, an age-old set of unwritten rules also determine how the race develops.

We’ll forgive you for being confused by these. As we saw in the Pyrenees in 2003 and 2010, they are incredibly open to interpretation and often create more problems than they solve, but we thought that we’d take a look at some that you might find mentioned during this year’s Tour de France.

First, and most confusing of all…

You can’t attack the maillot jaune when the following happens…

They crash: If the leader of the race goes down in a crash then don’t you be thinking about attacking until they are safely back in the bunch. But that’s only if the racing hasn’t really kicked off yet, of course.

If the peloton is lined out with riders fighting to stay in contact, then it’s fair game (sometimes). Even during the heat of battle, a truce can be achieved if those at the front believe that a rival has been hampered by circumstances beyond their control.

How does this get decided? As we saw in 2003 with Ullrich, who stood the most to gain from Armstrong’s misfortune, the riders at the front usually decide, following a lot of conversation and hand waving.

They suffer a mechanical problem: Like a crash, this one is subject to the race situation at the time of the incident. If the racing is on, with the pace high and attacks already flying off the front, then the yellow jersey just has to get on with it and get back to the front of the race.

In fact, mechanicals are considered by many to be simple bad luck. Contador attacking Schleck in what became known as ‘chaingate’ is the perfect example of this. One side of the argument (and believe me, this went on for weeks back in 2010) says that Contador showed the ruthless instinct of a winner while others reckoned that it was bad form to take advantage of Schleck's chain coming off. You just shouldn’t have dropped that chain, Andy!

But (just to confuse matters further) when Chris Froome shipped his chain in 2017, Fabio Aru – who had hit the front just as the Team Sky rider glanced down at his misfiring bike – was chastised by his rivals, who ordered the Italian champion to call off his attack until Froome had regained his place in the group.

The bottom line? Normally, the riders adhere to the unwritten rule that a Tour de France should not simply be won by luck or through another rider’s misfortune…

Unless, of course, your rivals want to gang up on you to force you out of yellow; a fate suffered by French hope Jean-François Bernard at the 1987 Tour, who shipped a chain and then punctured just as Stephen Roche, Pedro Delgado and a few others took flight on the way to Villard-de-Lans. He never saw them, or yellow, again.

I told you it was complicated…

They stop for a nature break: This one, thankfully, is a bit more straightforward (mostly). If the start of a stage has been fast and a small group has gained a small advantage over the peloton, the yellow jersey stopping for a piddle is the sign that the peloton will now relax and let the breakaway take a few minutes' lead.

A collective sigh of relief will be released around the peloton when the yellow jersey's hand goes up. Riders of a team that has failed to make the breakaway may now quietly remove their radio earpieces as the team manager won’t be best pleased.

Of course, while this particular unwritten rule tends to be followed religiously, sometimes a poorly timed nature break (and some opportunistic tactical manoeuvring on the part of rivals) can prove fatal to a race leader.

Just ask Demi Vollering, who stopped for a pee alongside her SD Worx teammates on stage six of this year’s Vuelta Femenina, only for Annemiek van Vleuten’s Movistar team – instigating a pre-planned tactic, they later claimed – to begin drilling it on the front.

That conveniently timed attack proved enough, just, for Van Vleuten to take the overall win, despite her younger compatriot looking stronger throughout the week, and prompted Vollering to accuse the world champion of breaking one of cycling’s most sacred unwritten rules. The SD Worx leader may have been furious, but Van Vleuten was the winner. And, at the end of the race, that’s all that matters.

Drafting is ok(ish)

Coming back from a crash, mechanical or nature break will require a racer to ride at a speed faster than the peloton. That’s difficult, so the rider will take a draft in the convoy of team cars to make things easier. This is actually not allowed, but the race jury generally turns a blind eye as otherwise they’d have half of the peloton disqualified for being outside of the time limit every day.

But sometimes the race jury notices, and then drafting a car is suddenly not ok. This is usually when the racing is at a critical stage, or if a rider is taking an unfair amount of time behind their team car. Sounds woolly at best? It is.

Poor old Nils Eekhoff was disqualified from the U23 World Championships after he had crossed the line first. The jury decided that his drafting of a car with 125km left to race – after he had crashed and waited to be examined by the race doctor – constituted a breach of the rules.

The whole situation made many question the jury’s decision, though others were simply frustrated by the lack of consistency around the enforcement of this rule.

Speaking of a lack of consistency…

During the second stage of last year’s Tour, when the race was still in Denmark, a ‘barrage’ was called by the commissaires (ordering team cars out of the gap between the peloton and a chasing group, so the chasers can’t take advantage of the cars’ draft) as Rigoberto Uran attempted to regain contact following a crash on a bridge, but not when race leader Yves Lampaert went down. Murky indeed.

You scratch my back…

If you’ve ever looked at a bike race and wondered why certain riders are working in the breakaway and others aren't, the answer is often that they're trying to achieve different things.

One rider might be chasing the mountain points on offer at the top of climbs, while another needs the points from the intermediate sprint. These riders won’t contest the other rider’s competition, though all are expected to shoulder an equal workload in the effort to keep the breakaway ahead of the peloton.

Once a rider has collected all of their points available for that day, they may well give their breakaway companions some extra help on the front of the bunch, especially if those riders have allowed them to take points uncontested.

This unwritten rule is highly nuanced and full of sub-plots and mini rivalries.

The peloton will decide when to race

The peloton has in the past decided to neutralise the race if they feel that it is too dangerous. This can be because of poor road conditions, extreme weather or because of too many crashes. We've also seen protests to highlight danger in races, such as the mini stoppage that happened at the beginning of stage four in 2021 following a number of terrible crashes in the preceding days.

Stage one of the 2020 Tour saw a downpour on roads that hadn’t seen rain in several weeks. The result was a number of crashes, and the decision was taken to neutralise a descent to the finish before the race started again on the flat run to the line.

In situations like this, the peloton will turn to its 'patrons'. In years gone by, this would have been one dominant rider – Merckx, Hinault, Cancellara – but today there isn’t one voice that controls proceedings. Instead, senior riders and road captains like Luke Rowe would collectively agree to take that decision, and the peloton follows their lead.

When Astana’s Omar Fraile decided to ignore this and push the pace on the descent, he received quite a bit of abuse as he was absorbed by the peloton.

The final stage is a procession... until it isn't

There is absolutely no written rule that states that the final stage of the Tour de France should have no outcome on the overall race, but this is the way it has been for years. The final day is reserved for sipping champagne, taking team pictures, and generally rolling along at a speed that makes half the peloton nervous about missing their flight home.

Generally, the race starts just outside of Paris and rolls at this leisurely speed until the riders hit the Champs Elysees (or when the Eiffel Tower comes into view, as tradition dictates). The team of the yellow jersey usually leads the race across the finish line on the first lap, though a rider that is retiring may be allowed to roll off the front for the honour.

After that, the eight laps up and down the famous boulevard are suddenly a proper race again with attacks that are almost certain to fail, heading up the road before the sprint is won and the race is finished.

However, with the 2024 Tour de France set to finish in Nice to avoid a clash with the Paris Olympics, we may finally be treated to some ‘proper racing’ - with maybe even the yellow jersey up for grabs - on the final day for the first time since 1989… We can hope anyway!

A benevolent yellow jersey

It may seem hard to believe now, in an era when Tadej Pogačar and Jonas Vingegaard appear intent on gobbling up everything before them at the Tour, but there was a time when the dominant rider at the Tour de France was expected to share the love around the peloton, and dole out favours and stage wins like a yellow-clad Father Christmas.

That tradition arguably began in the early 1990s, when Big Miguel Induráin eschewed the cannibal-like instincts of Merckx and the iron-fisted bravado of Hinault for a more genteel form of domination, bartering stage wins and fleeting glimpses of glory to his fellow riders for an easier passage through five straight Tour victories. He was going to win anyway, so why be greedy?

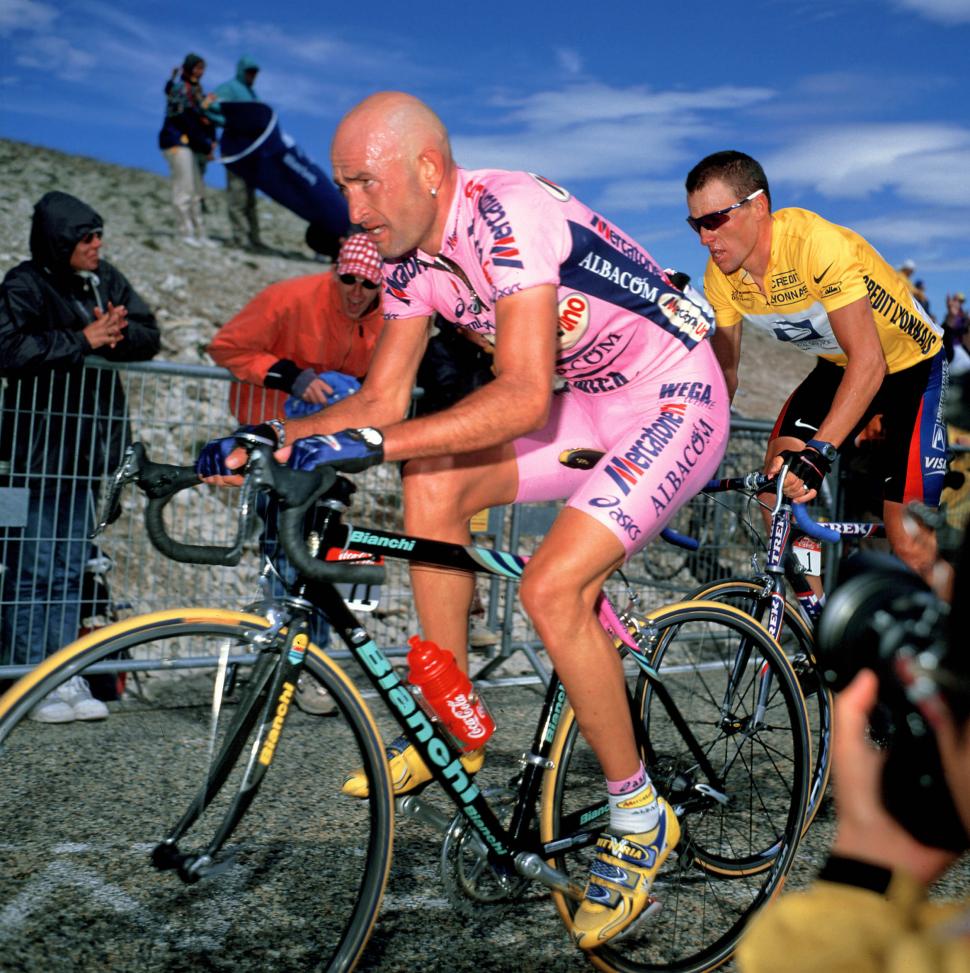

Even Lance “No Gifts” Armstrong carried on that tradition for the most part, letting the likes of Ivan Basso, Alejandro Valverde, and Marco Pantani cross the line ahead of him (though he quickly came to regret letting Il Pirata beat him to the top of the Ventoux in 2000).

Vingegaard, meanwhile, notably eased up during last year's final time trial to gift the win to teammate Wout van Aert, though doesn't seem as yet minded to dole out favours to rivals. Pogačar, for his part, appears to have no need or desire to curry favour with the peloton either. Perhaps they’ll both mellow in their old age?

Café wisdom: road.cc readers on unwritten rules of the Tour de France

In a previous edition of this feature, kil0ran added to our list of unwritten rules with these unconventional traditions:

"If you pick up a jersey due to a penalty you must make clear that it's not how you'd like to have won it.

"See also the rare occurrence of the maillot jaune (or any maillot) being unable to start the next day due to injury. Or disqualification."

kil0ran's point about a race leader abandoning while in the leader's jersey was even raised at this year's Giro d'Italia.

Cycling tradition dictates that if a rider finishes a stage in the overall lead but fails to start the next day, no-one should wear the yellow jersey on that stage – as it has yet to be earned by anyone other than the unfortunate DNSer (once that stage finishes, it’s good to go of course).

At the Giro, however, Geraint Thomas rocked up after the rest day in the pink jersey, despite race leader Remco Evenepoel only pulling out with Covid following the stage nine time trial.

I suppose jersey sponsors have paid their money for a reason…

Clear as mud, isn't it? If you have any more unwritten rules to add, let us know in the comments!

Main image: ASO, Pauline Ballet

After obtaining a PhD, lecturing, and hosting a history podcast at Queen’s University Belfast, Ryan joined road.cc in December 2021 and since then has kept the site’s readers and listeners informed and enthralled (well at least occasionally) on news, the live blog, and the road.cc Podcast. After boarding a wrong bus at the world championships and ruining a good pair of jeans at the cyclocross, he now serves as road.cc’s senior news writer. Before his foray into cycling journalism, he wallowed in the equally pitiless world of academia, where he wrote a book about Victorian politics and droned on about cycling and bikes to classes of bored students (while taking every chance he could get to talk about cycling in print or on the radio). He can be found riding his bike very slowly around the narrow, scenic country lanes of Co. Down.

Is it any wonder that drink driving is still a problem when the police do nothing even with clear evidence like this: https://youtu.be/hw071PAofHQ

Such as, for example, saying: "It’s made from two types of fabric: super-loud yellow (orange is also available as a colour option, as is pink in...

Possibly, but I think there will still be a time delay between receiving a warning and looking and the brain processing the image.I guess cycling...

Gutted

Re the ESPN Chappy....

Indeed - but again these are perhaps questions we should keep asking. Even if the immediate answer is "well we are where we are" or "how on earth...

Specialized aren't that American. Merida owns something like 49%.

Then smash bad driving behaviour very hard...

Calls for Oxfordshire transport chief to resign blocked...