- News

- Reviews

- Bikes

- Accessories

- Accessories - misc

- Computer mounts

- Bags

- Bar ends

- Bike bags & cases

- Bottle cages

- Bottles

- Cameras

- Car racks

- Child seats

- Computers

- Glasses

- GPS units

- Helmets

- Lights - front

- Lights - rear

- Lights - sets

- Locks

- Mirrors

- Mudguards

- Racks

- Pumps & CO2 inflators

- Puncture kits

- Reflectives

- Smart watches

- Stands and racks

- Trailers

- Clothing

- Components

- Bar tape & grips

- Bottom brackets

- Brake & gear cables

- Brake & STI levers

- Brake pads & spares

- Brakes

- Cassettes & freewheels

- Chains

- Chainsets & chainrings

- Derailleurs - front

- Derailleurs - rear

- Forks

- Gear levers & shifters

- Groupsets

- Handlebars & extensions

- Headsets

- Hubs

- Inner tubes

- Pedals

- Quick releases & skewers

- Saddles

- Seatposts

- Stems

- Wheels

- Tyres

- Health, fitness and nutrition

- Tools and workshop

- Miscellaneous

- Cross country mountain bikes

- Tubeless valves

- Buyers Guides

- Features

- Forum

- Recommends

- Podcast

review

£16.00

VERDICT:

A beautiful film about one of pro cycling's biggest tragedies

Weight:

30g

Contact:

At road.cc every product is thoroughly tested for as long as it takes to get a proper insight into how well it works. Our reviewers are experienced cyclists that we trust to be objective. While we strive to ensure that opinions expressed are backed up by facts, reviews are by their nature an informed opinion, not a definitive verdict. We don't intentionally try to break anything (except locks) but we do try to look for weak points in any design. The overall score is not just an average of the other scores: it reflects both a product's function and value – with value determined by how a product compares with items of similar spec, quality, and price.

What the road.cc scores meanGood scores are more common than bad, because fortunately good products are more common than bad.

- Exceptional

- Excellent

- Very Good

- Good

- Quite good

- Average

- Not so good

- Poor

- Bad

- Appalling

Pantani: The Accidental death of a Cyclist is a lyrical, honest commemoration of one of modern cycling's most tragic figures.

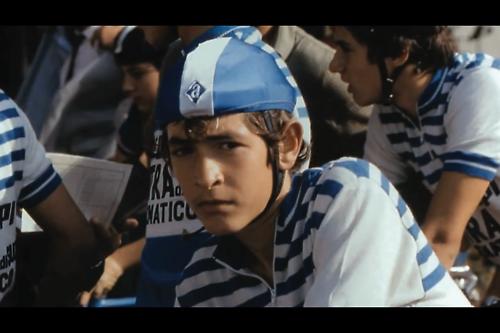

It’s ten years since Marco Pantani died at the age of 34 - face down in a mound of cocaine, holed up alone in a off season Rimini hotel room, too paranoid and depressed to see friends or family.

To some cycle fans Pantani will always be preserved in 1998, the great Italian hope, a cheeky little imp sandwiched between the pillars that were Miguel Indurain and Lance Armstrong. To most fans he was just another drug cheat, coated in the flamboyance and gamesmanship so beloved of the Italian sporting public. An earring and bandana-sporting chancer sandwiched between two more cunning riders and ultimately unlucky enough to get caught doping in a time when redemption and a book deal were still a long way away over the horizon.

The deification of a doping sportsperson never feels right but to its credit Pantani: The Accidental death of a Cyclist isn’t a simple hagiography. Based on Matt Rendell’s exhaustive biography and with fine commentary from both Rendell, with his precise and sad delivery, and the crisp, no nonsense school master style of Richard Williams, the triumph and ultimate tragedy of Pantani’s career is delivered in a tight and lean 96 minutes.

Pantani: Accidental Death of a Cyclist is named in homage to the Dario Fo play Accidental Death of an Anarchist, a study of morality and bureaucracy in which plenty of people are complicit in a death that none of them need take responsibility for. As such, it’s a perfect metaphor for the desperate state of pro cycling over the past twenty years and reminds us that Pantani’s talent and spirit still represent why cycling as a sport is so exhilarating and why his early death is more than just a simple cautionary tale of one person’s lack of responsibility.

The first stylistic hurdle of biographical film making is how the dickens you are going to marry lots of bits of old footage of varying quality with more recent interviews with friends and family and try to fill in the gaps where no footage exists? The modern disease of stretching footage with slow motion to fit narrative is thankfully absent. James Erskine fills the gaps with beautiful, slightly time lapsed epic mountain mist shots, and a convincing Pantani lookalike using replica kit and bike for obliquely photographed training scenes to support archive footage.

Beginning with time ticking thriller music tinkling over mountains brooding with mist we’re taken back to Pantani’s first major display of intent at the 1994 Giro. Indurain, like a mechanical golem, is grinding on his way to a second consecutive Giro/Tour de France double when the fans lining the climb are presented with something fresh: a diminutive climber who can attack and then attack again at will.

At just 24 Pantani was a balding and slight figure - as Rendell remarks almost “frail looking” - but he leaves Indurain and the field for dead on the Mortirolo that day and the fans celebrated an Italian stage win delivered with showmanship and swagger. Even now, watching Pantani’s fluid acceleration on the drops is a thing of beauty and we’re reminded that his descending skills were extraordinary and terrifying too.

Rendell suggests it was like a return to the past panache of Coppi and Bartali. “He restored a kind of magic to the sport. It was like going back 50 years,” he says. Pantani won two stages of the Giro that year and became, as Erskine remarks “that single figure who represents the emotions of a country at a certain time”.

Coming back from a horrendous crash in 1997 to take the 1998 Giro and Tour de France double, Pantani was a god in Italy for less than a year before failing a haemocrit test during the 1999 Giro and being quickly ejected by the sport and rejected by the fans. Staging a come back and seeking forgiveness by tackling a methodically doping Armstrong on Ventoux in 2000 finally destroyed Pantani’s fragile psyche.

You may argue that a cyclist with haemocrit levels estimated to be around 60% for most of his successful career should not be recognised as admirable but Erskine reminds us that Pantani wasn’t just a pack rider aiming to keep up. He was an exceptional athlete wrestling with the terrible choice of only being able to express his huge talent by conspiring with lesser talents enhancing themselves to beat him. Unfortunately Pantani wasn’t as clever as Armstrong and unlike Armstrong when caught he couldn’t keep his conscience locked in a box.

Erskine came across the last filmed interview with Pantani which shows the depth of his confusion and paranoia - to Pantani’s credit, still being expressed more as sadness than defiance.

Mark Kermode writing for The Guardian called the interviews with Pantani’s mother Tonina “heartbreaking”. They certainly are. She recalls her son’s disquiet when he first signed for Carrera and he realised what the trap was when competing at the highest level. “He said, ‘I am quitting. It’s a mafia.’”

But Pantani’s betrayal was also his parents betrayal. Tonina’s plea that “sport should be a healthy activity” distils the battle against doping down into a simple parental choice: stop your child from doing what they love or give in and accept the corruption of both your child’s ideals and their body.

Pantani’s story is one of the great tragedies in sport and so often tragedy is a matter of timing. With Armstrong still fighting one court case after another, the abiding tragedy of Pantani’s miserable death - silenced and ostracised by the sport and fans alike - was that he might have been saved just two years later.

After being stripped of the 2006 Tour de France, Floyd Landis exhausted his options and began naming names that could no longer be ignored or expelled in shame anymore. Today Pantani could have written the best exposé of the sport yet but ten years ago you didn’t get to turn on the mafia and walk away. Silence became Pantani’s only position and his guilt and regret took care of the rest. Rendell sums it up neatly: “The shame he felt led to his complete self destruction.”

Pantani: The Accidental Death of a Cyclist is both a beautifully crafted celebration of an extraordinary talent and also a lament for a simple soul twisted and then ruined by a sport working in denial. It’s hardly the legacy Pantani would have wanted but it may prove to be a worthy one all the same.

Verdict

A beautiful film about one of pro cycling's biggest tragedies

road.cc test report

Make and model: Pantani: The Accidental Death of a Cyclist Soda Pictures

Size tested: DVD

Did you enjoy using the product? Yes.

Would you consider buying the product? Yes.

Would you recommend the product to a friend? Yes.

About the tester

Age: 47 Height: Weight:

I usually ride: A 20 year old Condor Italia on the school run. My best bike is: Condor Moda Ti - summer bike

I've been riding for: Over 20 years I ride: Every week I would class myself as: Experienced

I regularly do the following types of riding: road racing, club rides, sportives, general fitness riding,

Latest Comments

- grumpyoldcyclist 4 min 20 sec ago

- because in fact cyclists have been prosecuted and convicted as above, so really he's talking nonsense (or at least needs to present some...

- Bigtwin 6 min 10 sec ago

I for one like your contribution. I mean, it's good to know that Tory ex-Home Secretaries are busy spewing bile into their keyboards at home, not...

- Bigtwin 33 min 24 sec ago

A smidge of £8.5K. Seriously. Someone needs to have a strong coffee.

- Bigtwin 37 min 10 sec ago

Business model innit? When they brought in hire bikes in our town, they approached the bike shop I was then running to so the maintence. It was...

- IanEdward 44 min 23 sec ago

Nice, tyre clearance AND 2x AND non-boring paint jobs, a good alternative to Giant Revolt/ Canyon Grizl....

- Hirsute 50 min 29 sec ago

For the first time, the Norwegian government has calculated the value to society of the health benefits of increased walking and cycling. ...

- graybags 56 min 50 sec ago

I managed to do 12 200k's over 12 months , but unfortunately didn't read the rulles, two were in the same month and I missed a month..................

- nodgedave 1 hour 1 min ago

Toddle off cynic. A great man posting about extremely awful things and you chose to say that? The UCI needs clinical experts like you ... toddle...

- SecretSam 1 hour 13 min ago

Said the spokesperson for Big Hookless

Add new comment

10 comments

Calling this film "beautifully crafted" is a bit of a stretch. Not a bad documentary by any means, but loses its way in the second half. In particular, the constant reuse of the 'dramatic reconstruction' doping footage at the end got a little old.

As a film, the Armstrong Lie is much better, and I could easily recommend it to non-cycling fans. This movie is best left to those who already have a passion for the sport.

Incredibly ill-judged documentary, considering the revelations of the last few years.

The documentary makers would rather indulge the late Pantani's (and his family's) belief that he was the victim of some grand conspiracy rather than face up to the fact that he was just one of an entire peloton of dopers who got busted and couldn't handle the subsequent shame.

Any suicide is a tragedy but when the lead 'actors' in the drama seem unwilling, even after all these years, to admit to themselves the truth of the matter then it only compounds the sadness.

3/10

You probably need to read the book to understand. The film is more pro-pantani than the book, probably in a need to get his parents to appear on it in person.

It is still a good film (6 0r 7 out of 10), but I actually preferred the Armstrong Lie....though that is hugely flawed too, and I am no Armstrong fan for sure.

IL PIù GRANDE DI SEMPRE L' ULTIMO VERO CAMPIONE DEL CICLISMO L' UTIMO CHE CI HA DATO LE VERE EMOZIONI IL VERO SPETTACOLO

PANTANI NON è MAI STATO SPAVALDO ERA SUPERIORE A TUTTI E TUTTI LO SAPEVANO E LO TEMEVANO

DAVA FASTIDIO PERCHè IL PALCOSCENICO ERA SOLO PER LUI , ERA TROPPO FORTE

That pic of him descending is terrifying.

I can see where it lost the half star: 30g! They could have at least made the case out of carbon.

It's a desperate shame that Pantani lost his life just as the cycling world was starting to throw off (some of) the shackles of the entrenched doping culture and recognise the depth of the underlying historical issues. No doubt he had personality issues, would have been a hard person to work with and it's difficult to condone how he approached the challenges, but in the context of the world back then he was a welcome sight battling for position on a number of levels.

If you haven't read the Rendell book that forms the backbone to this film, then I strongly recommend that… it's a staggering book of two halves, the rise and fall.

Hey - no spoilers. I'm going to see this in a few days time.

he dies in the end.